3.1 Summary of My Experiments

During the period from 2014 through early 2019, I sequenced over 600 samples of my microbiome. Inspired by the experiment in a 2014 paper by David Lawrence83, during most of that time I also carefully tracked the food I ate, my sleep, and other variables like activity or location. Most of my near-daily samples were of my gut, but I also regularly tested my skin, nose, and mouth. Since I’m generally healthy, I didn’t have a specific goal in mind other than to try to understand better what these microbes are doing, so many of my tests were taken while undergoing simple experiments, like eating a specific type of food or visiting a new location. While not necessarily up to the rigorous standards of a formal scientific trial, these “n of 1” studies on myself helped me discover several new interesting facts about my own microbiome, many of which appear to contradict other published studies. In addition, hundreds of people sent me their own test results, letting me compare many different microbiomes. And of course, I also followed the latest developments in scientific publications and the general press as I eagerly tried to learn more.

What follows is a brief overview of some of the key things I learned.

- The microbiome is highly variable from day to day, often moving in ways that appear indistinguishable from random.

- Broad trends are there if you look closely. I found many intriguing new results.

- It is possible to change your microbiome in specific circumstances.

- People’s microbiomes are frustratingly different from one another. A feature that seems to be true about one person may not apply to another.

3.1.1 Diversity

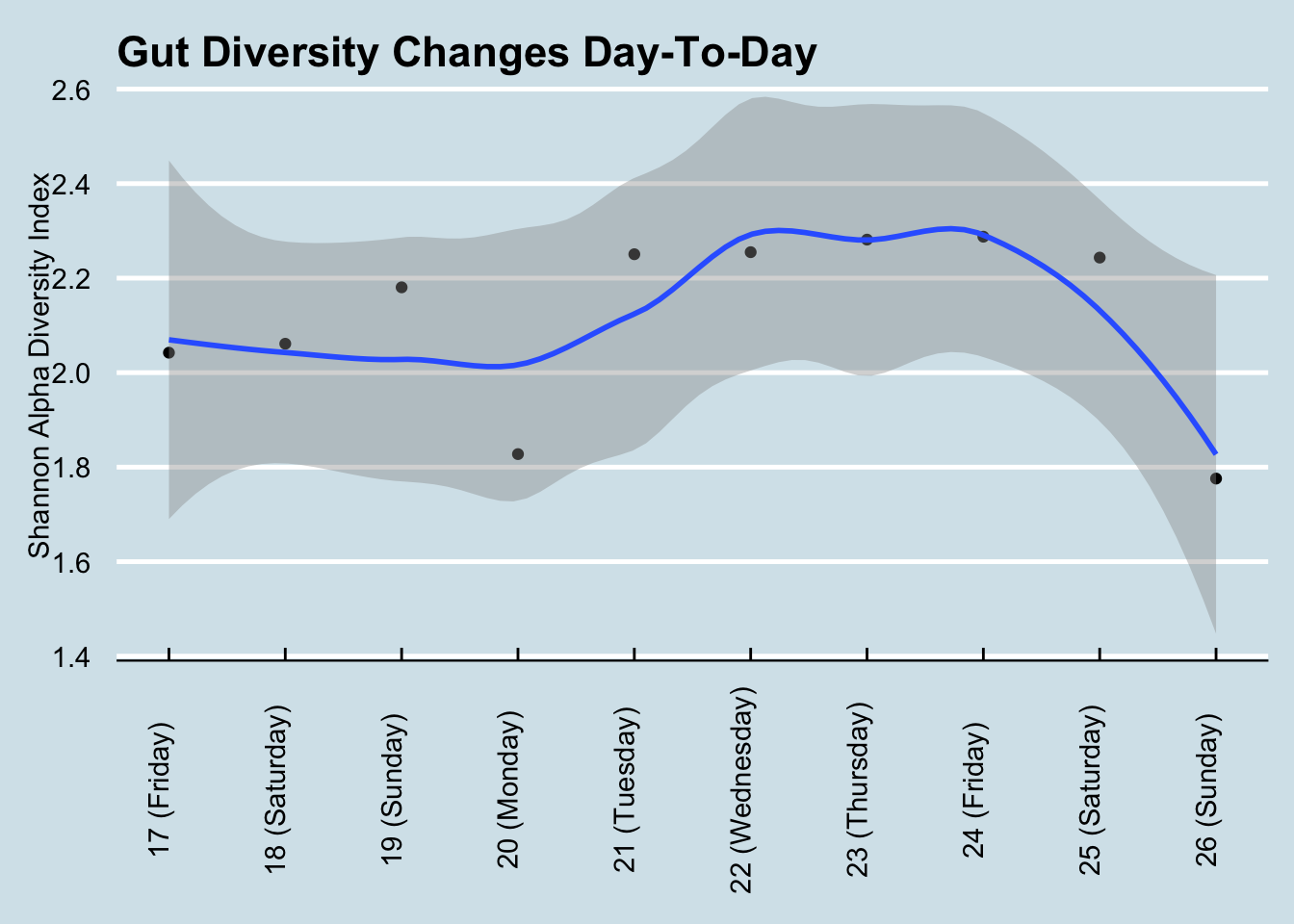

The general consensus is that diversity is good: a greater variety of microbes ensures more resillience against the daily threat of invaders. Many people, after taking just one test, often feel either reassured that their diversity is “good” or disappointed that it’s “bad”. But I find that day-to-day variability is high enough that it’s almost never useful to use a single result. For example, here’s my diversity during a typical week: (Figure 3.1)

Figure 3.1: Diversity changes significantly day-to-day.

If Monday were my only test, I may have been disappointed with my 1.83 score. Wait another day or two and, with no significant changes in diet, I was up to 2.29 – before plunging to 1.78 by the weekend. Moral: don’t take a single result too seriously.

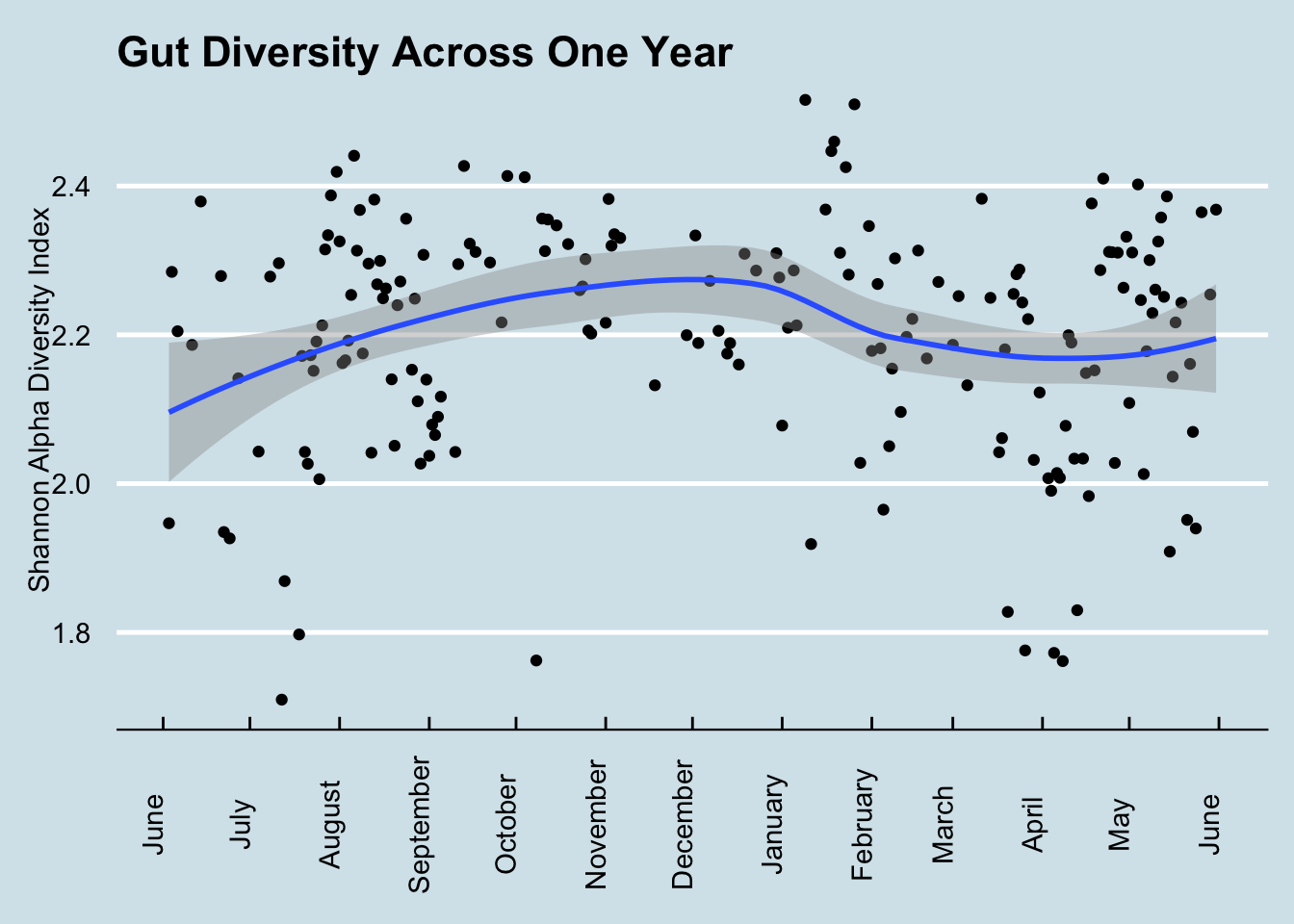

To get a sense of how much diversity can vary over a year (Figure 3.2)

Figure 3.2: Gut diversity varies day-to-day but holds to a recognizable range within a single individual

Although the blue moving-average line shows apparent stability, there are many days that are far above and below the average. Yes, at various times during this period I was eating different types of food, often in a deliberate attempt to influence my microbiome, but believe me: that is not the reason for the wild changes up and down. I also studied the mathematics behind how diversity is measured, hoping to find something more “accurate”, but ultimately I concluded that, like many attempts to summarize the microbiome in a single number, the whole concept of diversity is a mirage. Everything depends.

Another way to measure diversity is to simply look at the number of unique microbes. Since I began testing, I’ve found a grand total of 494 genera and 1276 species. About 249 unique genera are found just in my gut, and 63 unique ones were only in my mouth.

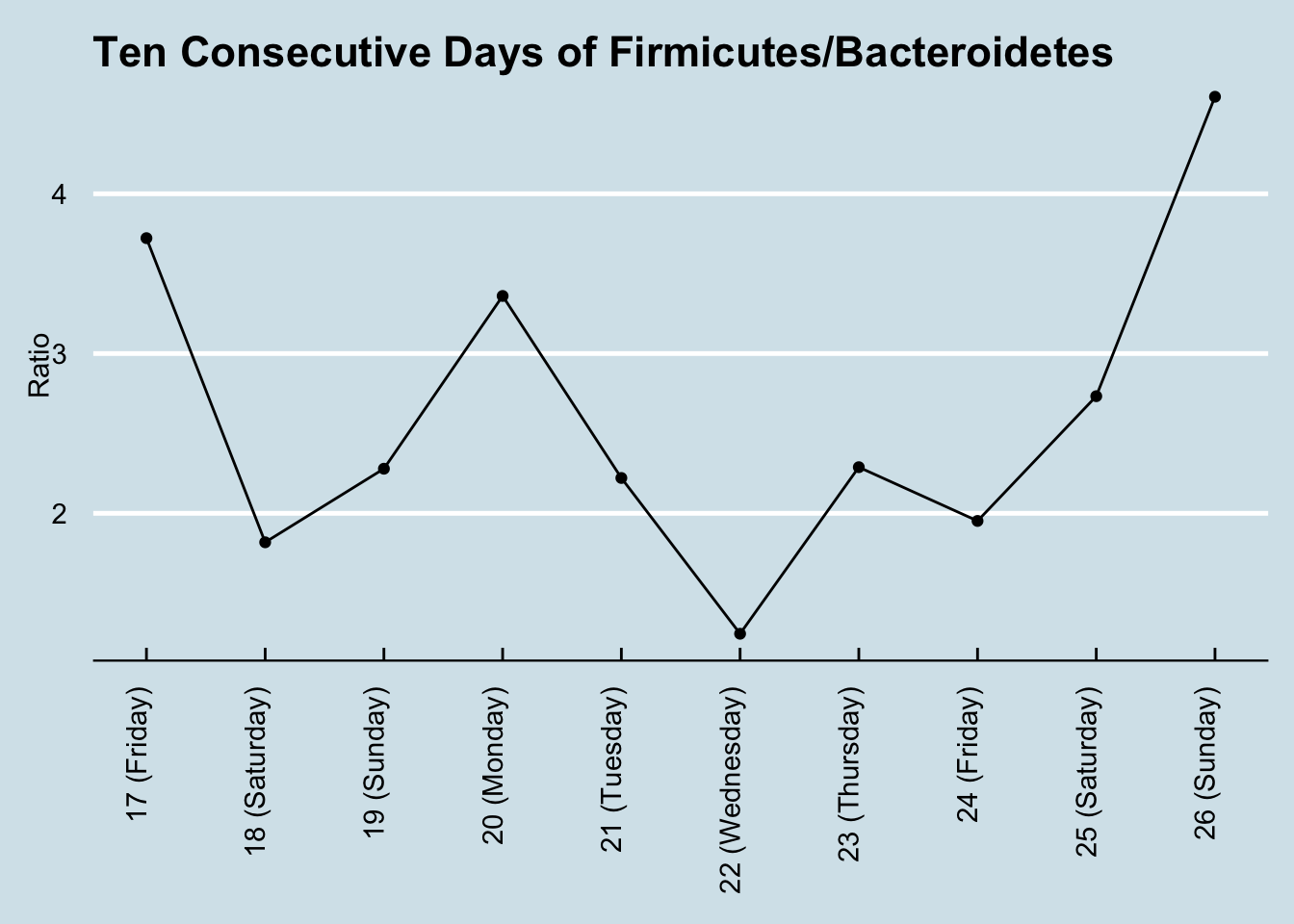

Another example of an idea that gets too much credit is the concept of a simple overall ratio as a way to explain or predict some aspect of health. The relationship between the two most common bacterial categories, the phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, is still often proposed as a key to understanding obesity despite its being resoundingly disproven in many studies.84

I confirmed this unreliability for myself, again obvious if you see how much variation there is day-to-day on a typical week (Figure 3.3)

Figure 3.3: The FB ratio changes significantly day-to-day, making it unclear which point should be relied upon over a ten day period.

I found high daily variability to be the case for just about every microbe that you’ll find mentioned in popular books or articles. Here are two more examples:

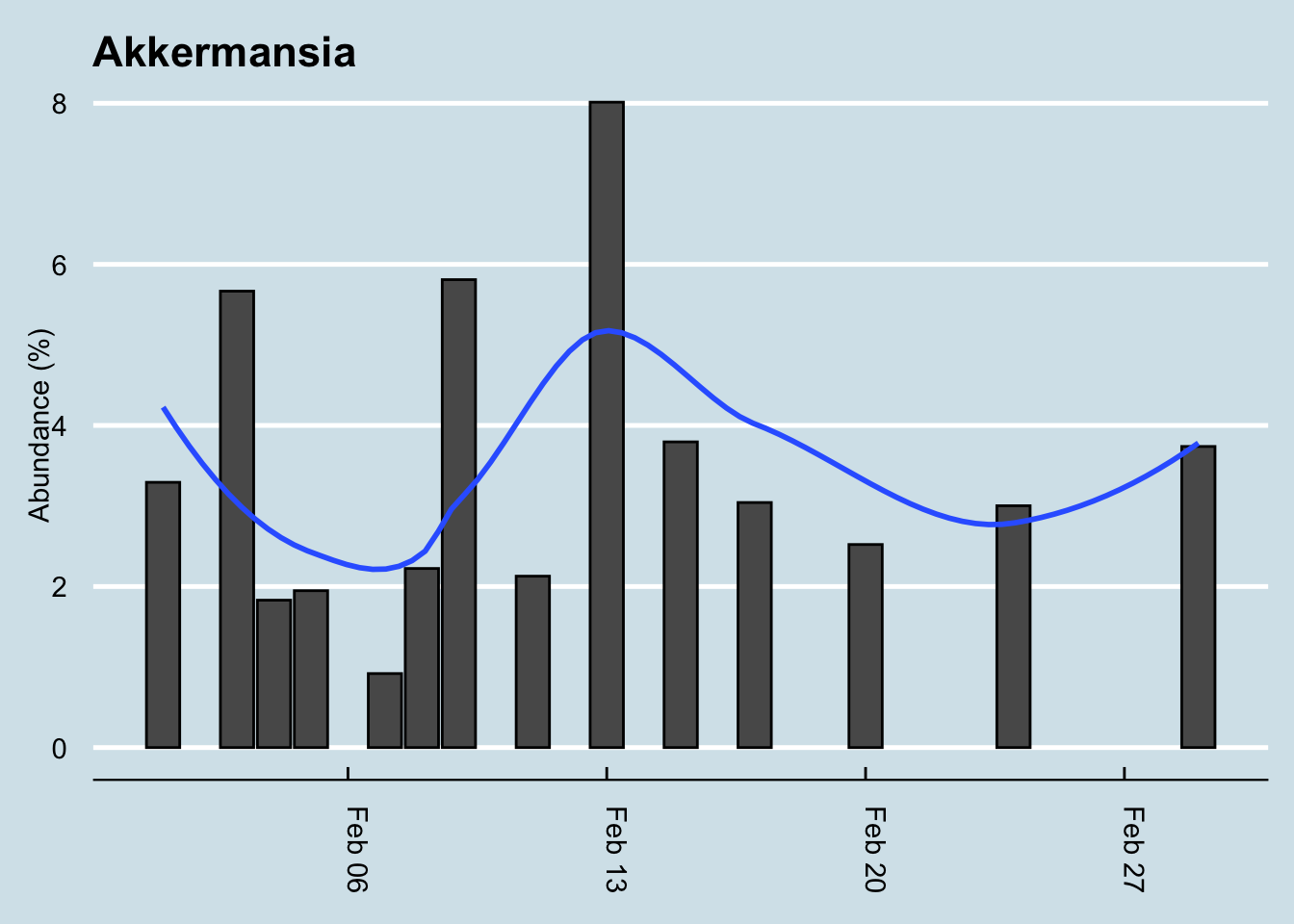

Akkermansia is a well-studied microbe due to its important role in degrading the mucin that lines the colon. There is only one known species of Akkermansia that inhabits human guts, Akkermansia muciniphila, so this is one of those cases when knowing the genus level is a pretty good approximation of what’s happening. Here are my levels over a typical month, with the blue line indicating the moving average.85.

I tend to have a much higher average abundance than most people. Later I’ll explain why I think that’s true, but first let’s look at another important microbe.

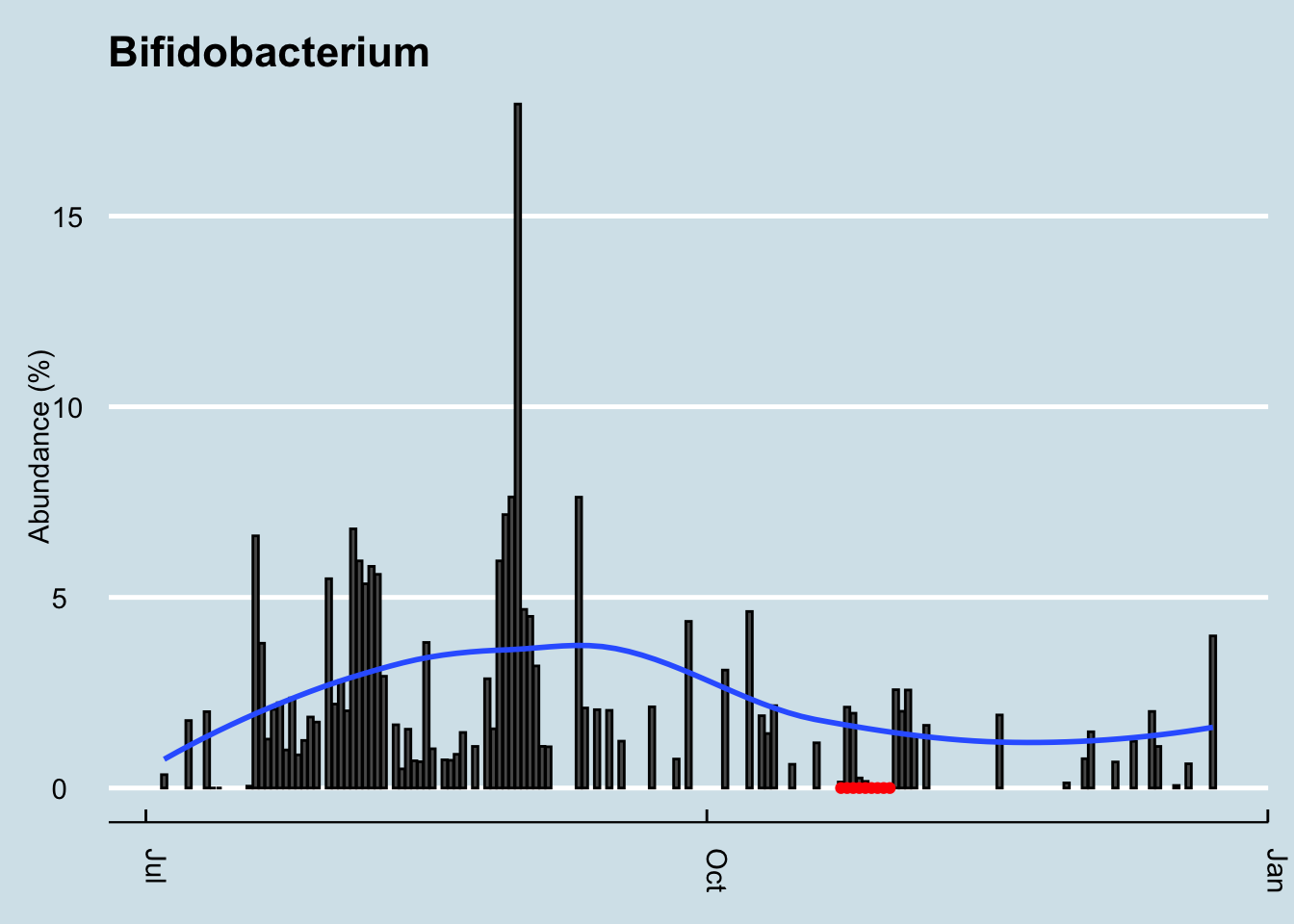

Bifidobacterium is a key component of virtually all popular probiotic supplements, partly because it is so easy to manufacture, but also due to its proven association with sleep and other aspects of health. A six month picture of my levels shows some dramatic ups and downs. (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4: Bifidobacterum levels over time. Red dots indicate period of taking probiotic supplements.

Incidentally, the red dots indicate days when I was taking a powerful probiotic supplement that contained Bifidobacterium. And that big spike in September? That was during a trip to New Orleans, when I ate a lot of red beans and rice. At least for me, food seems to work better than taking supplements.

What else did I discover? Here I get to the fun and rewarding parts of these experiments, because I did find several interesting microbes that are apparently unknown to science but that had a clear relationship to my activities.

The first is the yogurt drink kefir. Google the phrase “one of the most potent probiotic foods available” and you’ll find kefir in all the top results. A BBC documentary that tested people after consuming different types of “gut-friendly” foods found that kefir had by far the biggest effect. My interest piqued when, after my disappointment with kombucha, I spoke with a man who happened to mention his good luck with kefir as a solution to his many gut issues. On a doctor’s recommendation, he tried kefir for a number of years with limited success, until — frustrated with the $3/day expense of buying it at Trader Joe’s — he began making it himself at home. “What a difference!” he claimed.

Did it work for me? Yes! I found a very noticeable change in my gut microbiome — the most significant I’ve seen among my many experiments. Here’s what I found when I had the kefir drink sequenced:

| Kefir (%) | |

|---|---|

| Lactococcus | 96.06 |

| Leuconostoc | 3.02 |

| Lactobacillus | 0.22 |

| Faecalibacterium | 0.14 |

| Roseburia | 0.06 |

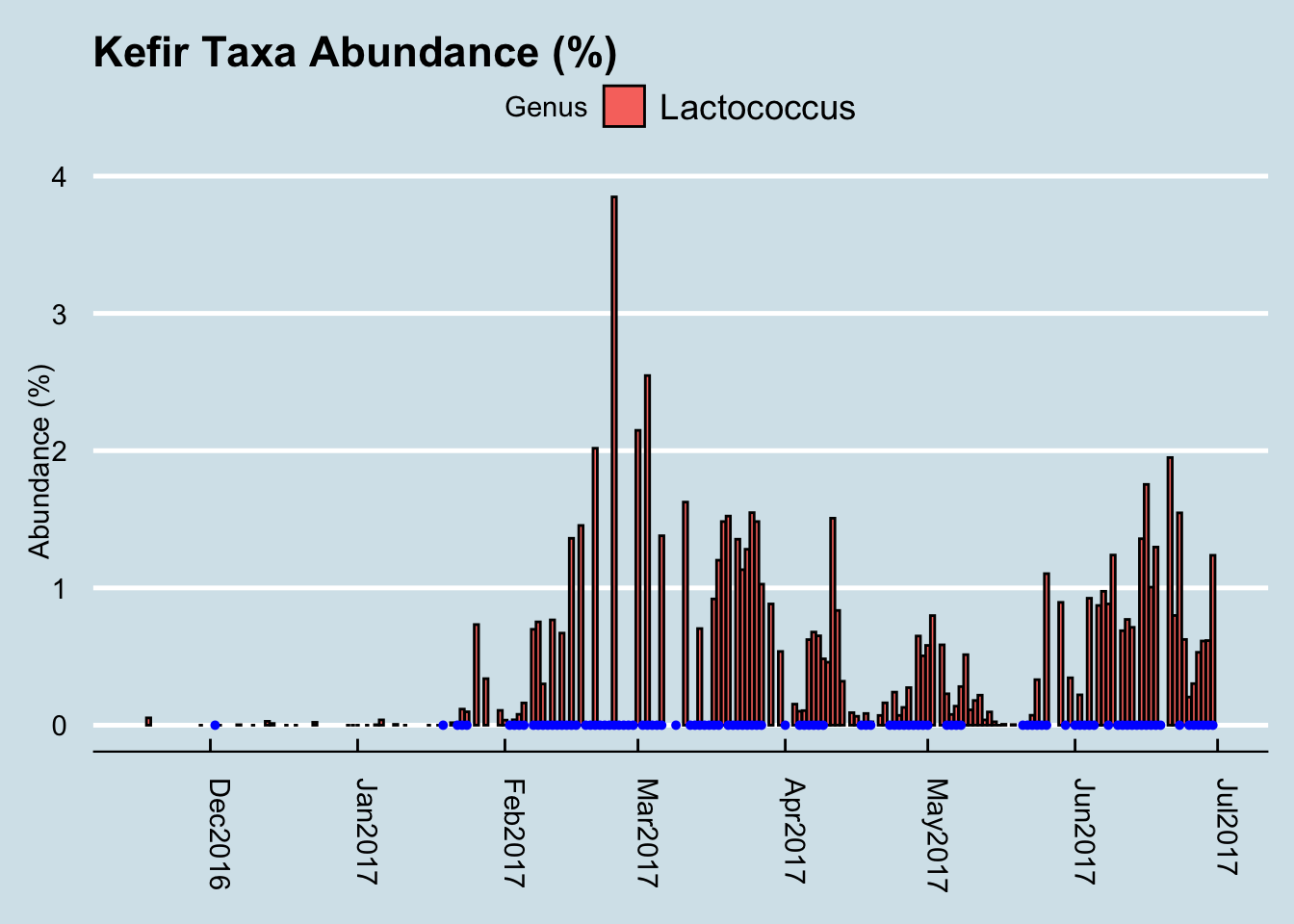

Look at my levels of Lactococcus, the main genus of microbe known to be found in kefir, and compare to what I saw in my gut biome:

The blue dots in the chart are days when I drank kefir. Since I sample near-daily over the entire chart, we can see that Lactococcus suddenly appeared shortly after I began to consume kefir. I had almost none beforehand. Also note that the levels seem to dip when I go for a few days without drinking any, such as during my business trips out of town in mid-March and another in early-April.

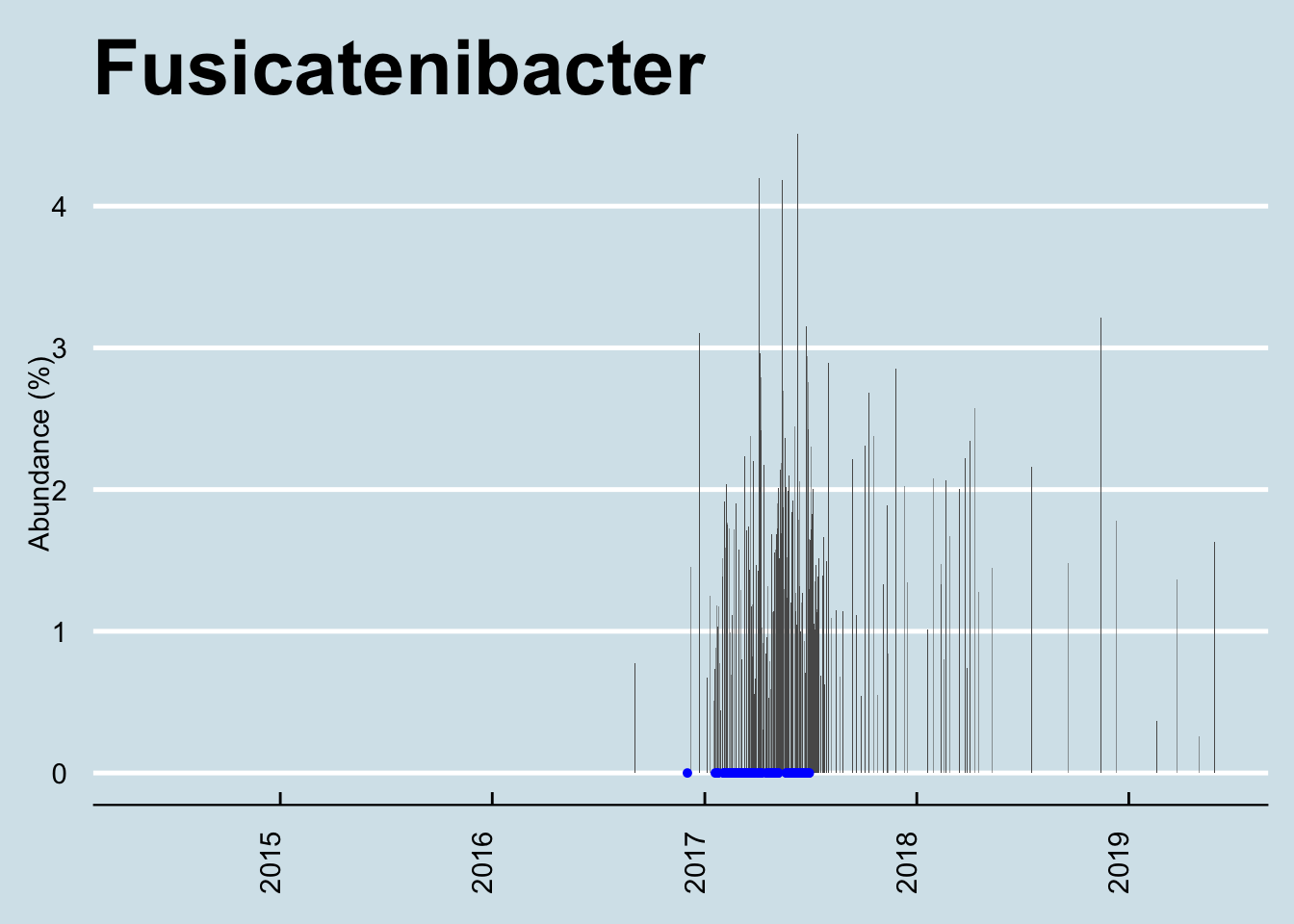

I was even able to find a new microbe, Fusicatenibactor that appears to exactly trace my kefir consumption.

I could find nothing in the literature that associates this microbe with kefir drinking. Though it appeared in me only after I started kefir, I found this microbe to be reasonably common among the hundreds of other samples people have sent, healthy and not, young and old. Why do I suddenly have it when I start drinking kefir, and why do others – even non-kefir drinkers – seem to have it? A mystery! Definitely something of scientific interest, though, and worthy of further investigation.

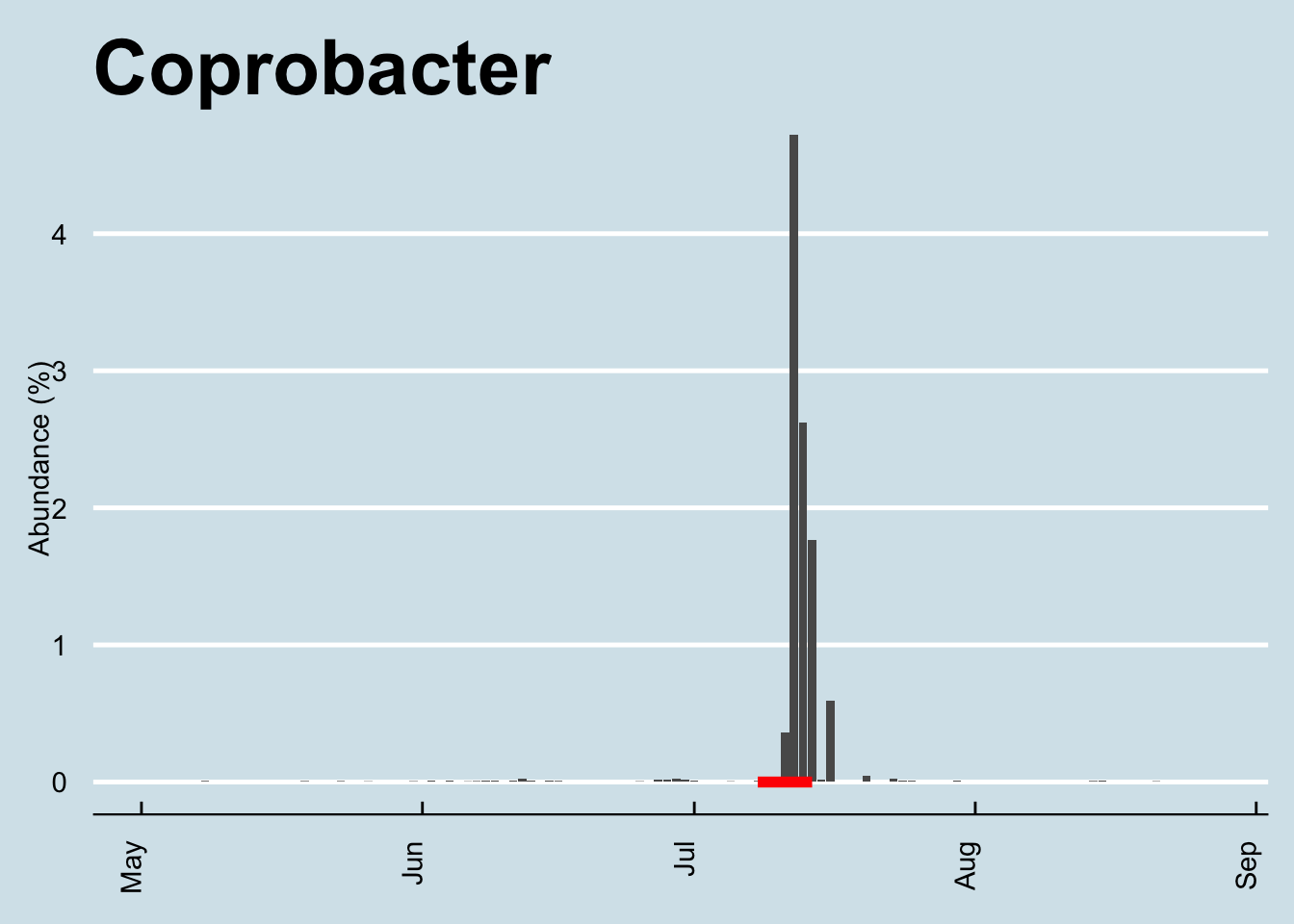

Here’s another odd microbe I found, this time during a trip to Beijing China (the red line):

I had none of this during my years of testing, but it suddenly appeared during the trip – and disappeared promptly afterward. Interestingly, although this microbe appears occasionally in the hundreds of other samples I’ve seen, there is no clear pattern, and never in the levels that appeared in mine. I couldn’t find any at all in the guts of two individuals I know who had been traveling in Asia.

3.1.2 Variability through time

Like most westerners, the vast majority of my gut is composed of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, with an occasional spike of Actinobacteria or Proteobacteria or Verrucomicrobia. You can see a detailed summary in the Appendix