3.11 Hacking my sleep

Most people know about the hormone melatonin and that it has something to do with sleep. Some international travelers take it to counter the effects of jet lag, and some people take it regularly as a treatment for insomnia. You might vaguely remember that it has something to do with the pineal gland, a small organ tucked near your brain, but did you know that your gut contains 400 times105 more melatonin? Something like 80% of its precursors, as well as those of the similar mood-regulating neurotransmitter serotonin are made in the gut106

There are other reasons to suspect that sleep and the gut may be linked. Think of all those home remedies for insomnia: a glass of warm milk before bed, apple cider vinegar, non-caffeinated herbal teas – many of these are foods known to affect the microbiome.

A quick internet search for “gut microbe serotonin” will lead you to Bifidobacterium infantis which modulates tryptophan, the stuff in turkey that urban legends have long (and incorrectly) blamed for that sleepy feeling you get after Thanksgiving dinner. If you can raise the level of B. infantis, might it also improve sleep?

To understand how to grow these microbiobes, it helps to understand something about the bacterium itself. Fortunately, it’s a well-studied organism, first identified back in 1899 as a common inhabitant of the intestines of breast-fed infants. Nowadays you can buy prebiotics that contain lots of bifido – or so they claim. Without rigorous lab independent verification of the claims, it can be hard to tell if the prebiotic form is helpful or not (and frankly, I’m skeptical)

Bifido is highly sensitive to oxygen, and flourishes best in environments like the colon that are anaerobic. It’s also a strong fermenter of certain types of starches, called resistant starch, so-called because they resist digestion.

One of the best resistant starches is plain old potato starch, made by finely grinding tubers into a light, white powder. You can buy an organic version from Bob’s Red Mill at most natural foods stores or high-end supermarkets. It’s cheap, and tasteless, so it’s often used in cooking, as a thickener for sauces.

Figure 3.30: No fiber in here.

The nutrition label on potato starch shows that it is essentially inert as a food. No calories, vitamins, or minerals, no fat, and not even any fiber. It’s just zero on everything, because it passes right through the stomach. When cooked, it becomes a thick, gooey consistency that quickly is absorbed by powerful stomach acids, but if kept in its raw state, it slides right through into the colon.

Not many other foods make it this far undigested, so a rich unfermented wad of fresh potato starch is a real treat for the Bifido of the colon and they quickly begin to make the most of it, fermenting it into the precursors to tryptophan. At least, that’s the theory.

Does it work? To find out, I started with two tablespoons the first day: just mix it in a glass of water (or other cold liquid107 and drink it, preferably in the afternoon to give it plenty of time to make it to the colon and start feeding the microbes. On the second day I raised it to three tablespoons and kept it there for the following days. Anything larger might risk unpleasant gas or loose stools until my body adjusts. Within two nights it was obvious that something was working. I couldn’t believe my excellent sleep!

After a few days, the sleep effect started to wear off, though I still felt much-improved. But could I trace the improvement to improved levels of Bifido? I continued to take potato starch randomly off and on for the next several months, measuring my sleep each night. What did the data say?

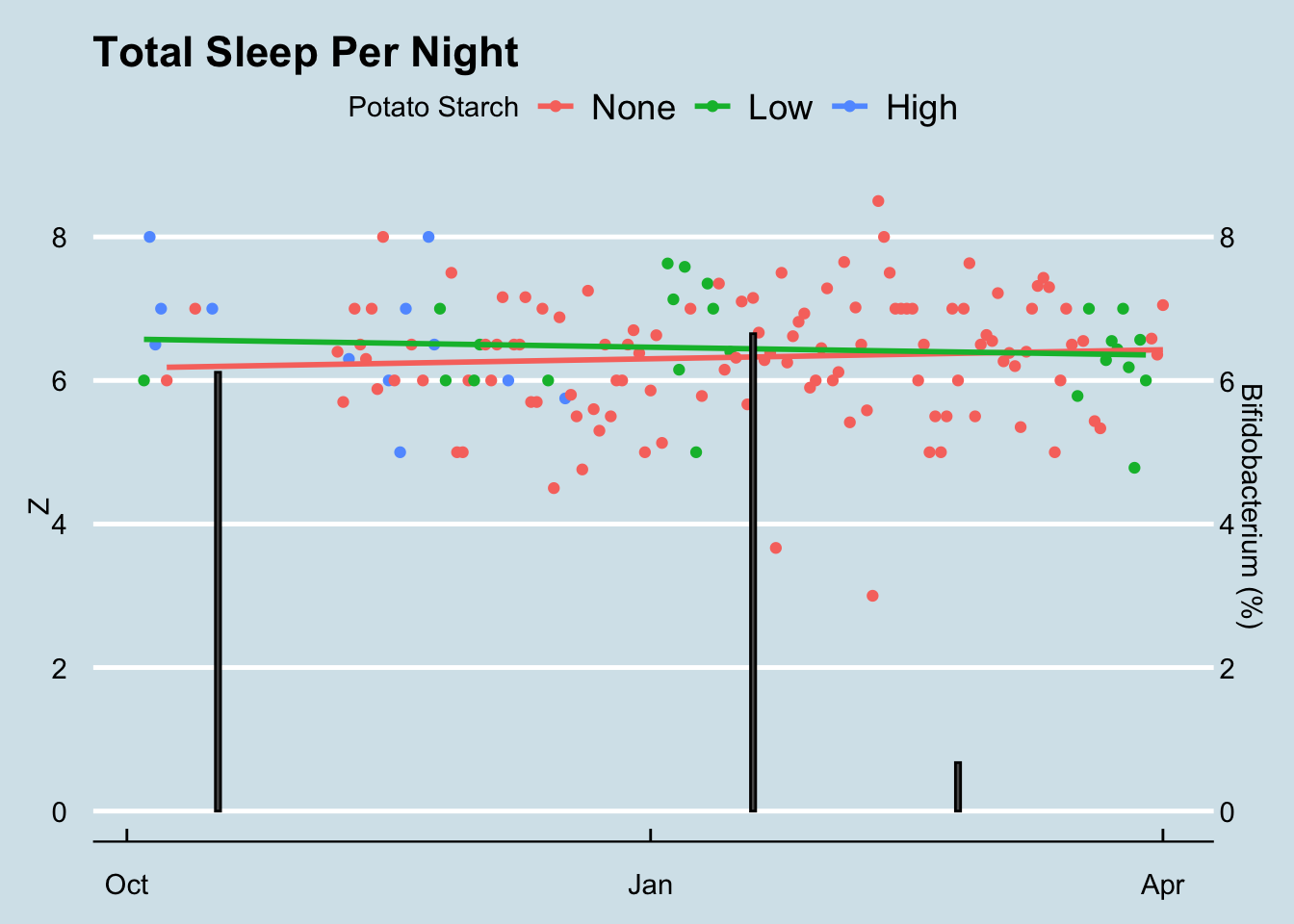

Figure 3.31: Potato Starch, Sleep, and Bifidobacterium levels.

As you can see, there is almost no difference in the total sleep I enjoyed on nights following my eating a tablespoon or two of potato starch. I studied the data carefully, looking for possible ways the potato starch may have had an effect, but couldn’t find proof that it worked108. It’s worth noting that the sleep times (Z) in my data are calculated with a Zeo sleep tracking device which I wore strapped on my forehead to detect the subtle changes in electrical activity that come with sleep. Zeo let me calculate precise REM and Deep sleep numbers as well, but none of them seemed to be affected by potato starch.109

Unfortunately, when I ran this experiment I only received three microbiome results. The first came shortly after beginning to ingest large amounts of potato starch so I don’t have a good “before” test. However, I do have one result taken after I had stopped the potato starch for several weeks. Both samples taken when consuming potato starch have much higher levels of Bifidobacterium than normal.

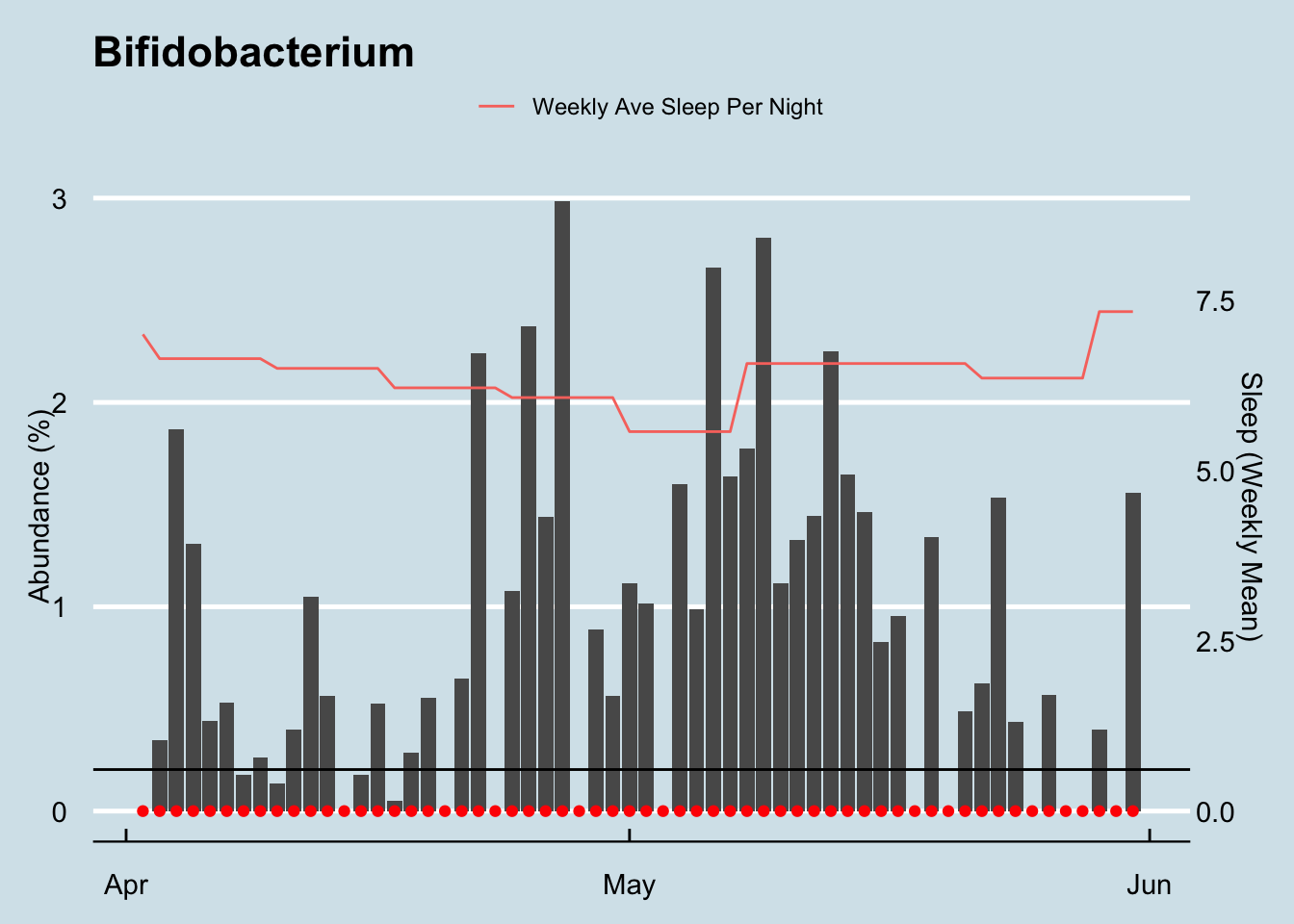

What is normal for me? Here’s how I look during a typical three month period. (Figure 3.32)

Figure 3.32: Bifido abundance over time. Red dots are days for which there is a sample. Blue line is the medium value for healthy people. Orange is the average sleep per night for each week.

Note that I have some Bifidobacterium in just about every sample (the red dots), but it doesn’t look like there’s a strong relationship with sleep. My daily average sleep (indicated in orange, averaged across the week) seems pretty constant, though the Bifidobacterium levels flucuate wildly.

Since describing my experiments, many people have contacted me to say they’ve tried the potato starch trick too with various levels of success. One person for whom it worked extremely well suggested from his own testing that the amount is critical. My 3-4 tablespoons per day was counterproductive, he said. The melatonin producers supposedly get swamped by that much food, so it’s better to give them a much tinier amount.

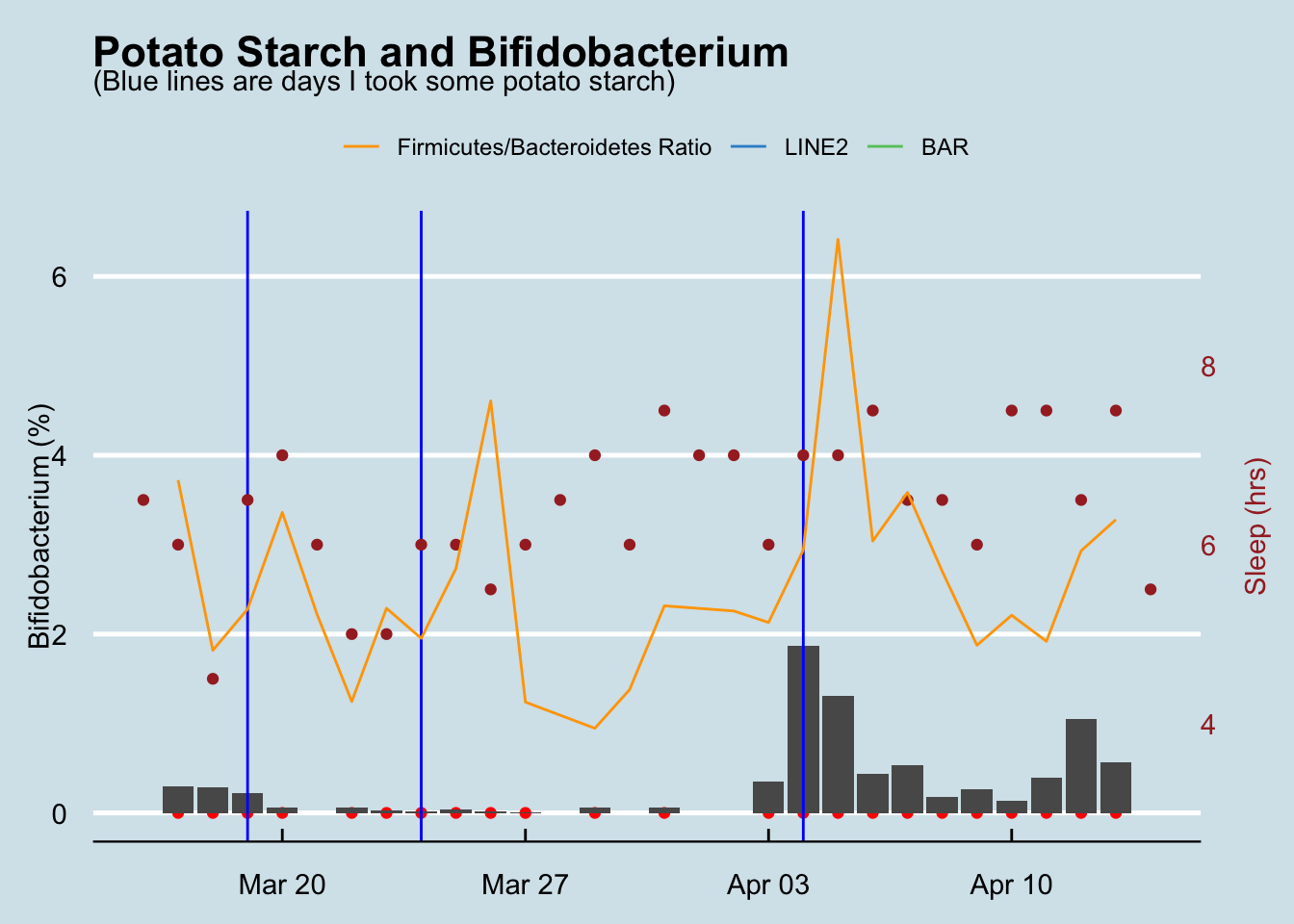

Unless you test daily, it’s hard to see subtle patterns in microbiome samples, and my original experiments weren’t frequent enough to tell why (or whether) the Bifidobacterium is changing. So, taking my friend’s advice, I tried some smaller amounts of potato starch. How do those look?

Figure 3.33: No apparent relationship between small amounts (1-2 tsp) of raw potato starch and Bifidobacterium abundance

Here it’s more obvious that any potato starch had little to do with the rise and fall of my gut Bifidobacteria. So why were the percentages so much smaller in this experiment than in the higher 6+% numbers I found while doing my original, more rigorous sleep measuring test above? Maybe it’s the tinier amounts? We’ll have to test again to understand for sure.

An interdisciplinary team of scientists says resistant starch can change the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes110. I calculated the ratio for my own testing and found some interesting, often dramatic rises a day or two after taking the potato starch. (Figure 3.33)

Conclusion: There’s a possibility that, in high enough amounts, potato starch increases my Bifidobacterium levels. Whether it increased microbes associated with melatonin production is less clear, but it’s hard to show that the potato starch caused a noticable change in my sleep.