3.4 Traveling to China

During my other international travel experiments, I tested only twice: before and after. Did I miss anything by not testing daily?

On a recent trip to Beijing, China, I took enough kits to test myself every day: gut, skin, nose, and mouth.

Any travel presents major challenges to the microbiome. Besides the significant differences in food, you are surrounded by different people (and germs) and weather. A trip to China involves a 12 hour plane flight too, exposing the body to a long period of lowered air pressure, tight quarters with people and recycled air, and of course the jet lag that accompanies a fifteen hour time shift. With all of that, it would not be surprising to see a significant shift in my microbiome.

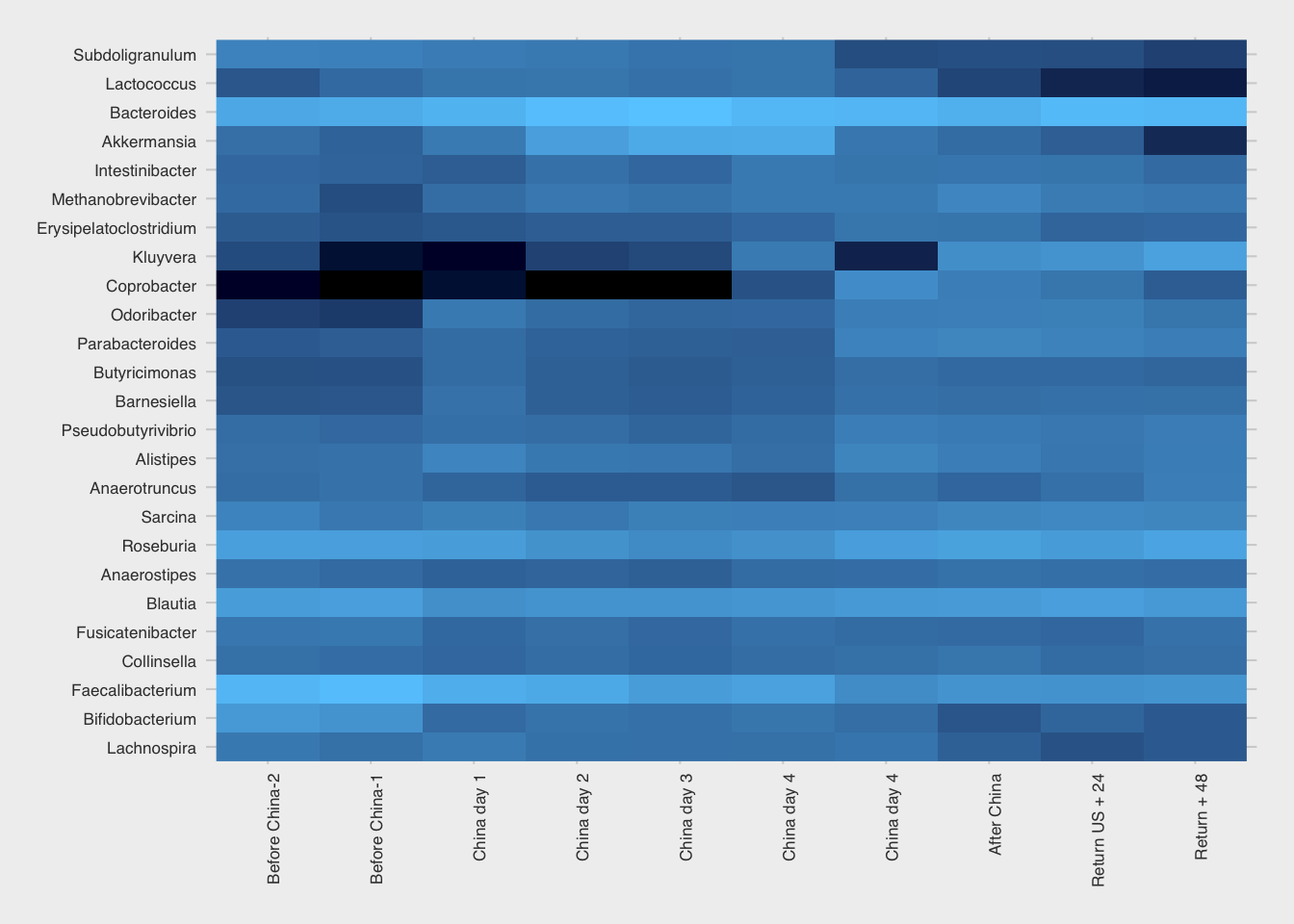

Here’s an overall heat plot of my gut, day-to-day before and after the trip 3.9

Figure 3.9: Gut samples before/during/after a trip to Beijing from the US. Dark is 0, lighter colors are higher abundance

I wasn’t surprised to see the rise in Kluyvera, a genus that on the 16S test can include sometimes-pathogenic species like E. coli or Shigella. These microbes can go up and down regularly, sometimes for no apparent reason at all, but often due to a significant change in environment, like on a trip where you’re exposed to many new microbes.

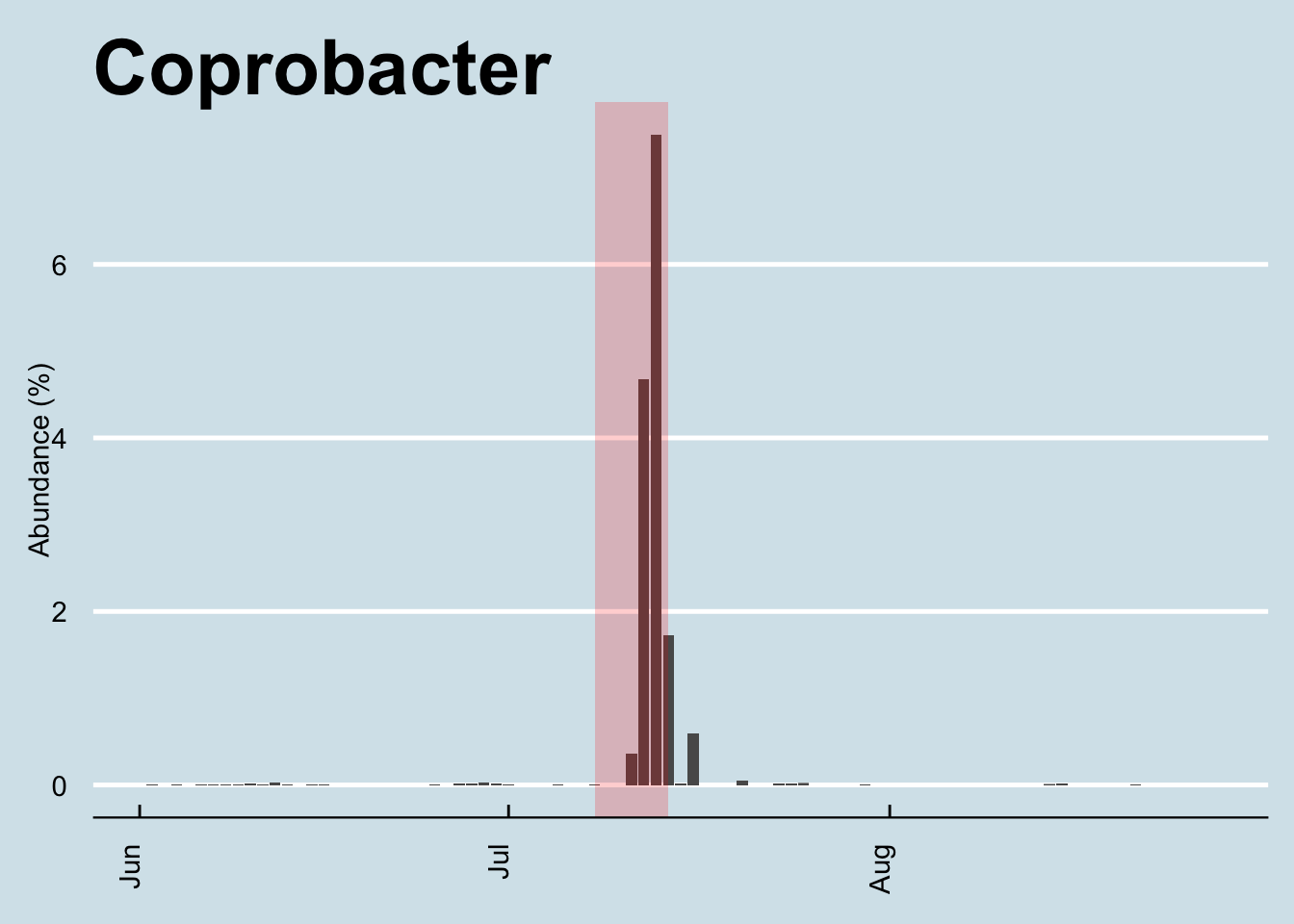

But the obvious standout is the genus Coprobacter, which soared beginning a few days after arrival and settled back after my return. I looked in my other samples over the long term and find that it is strongly associated with my China trip. 3.10

Figure 3.10: Changes in gut microbiome abundance of Coprobacter over time. Area shaded in red is the period while traveling from the U.S. to China.

Among my years of daily sampling it appears to have bloomed only once – this trip – after which it settled back to its quiet little self. The very first time I noticed any at all was early in the year, coincidentally (?) after I began drinking kefir. But even then, the amounts were tiny (under 0.01%) and often zero – until this trip.

When I looked at the hundreds of other samples people have sent me, I could find Coprobacter in just a few, and then only at relatively small levels (under 0.4%), less than a tenth of what I found on my biggest day (4.9%). The big 4000+ person Zhernakova study91 found it in small amounts in many people, but again, not very much. I couldn’t see any obvious patterns in any of the samples: some were from heavy travelers including some who had been to China, some not; some were from healthy people, some not. I found small amounts in a few skin samples (including my son, in a sample taken shortly after my return), but always in small amounts and with no clear patterns.

The natural question to ask about this microbe is what does it do? Unfortunately, as in so many of these cases, even Dr. Google can’t tell me much besides a few passing references in hundreds of top academic papers. It doesn’t seem to be a well-studied microbe. I know that it’s a member of the Bacteroidetes phylum, a “rod-shaped, gram-positive, obligate anaerobe”, and my particular species appears to be Coprobacter fastidiosus.

The Russian scientists who first isolated it (in 201392) found that, when cultured on glucose, it generates propionic, acetic, and succinic acids. If you look up what those acids do, you can invent lots of stories that might explain why it might appear on a trip to China (smelly? maybe the food! retinal modulation? maybe from the smog!). But I’ve been around the microbiome block enough times to know that you can explain just about anything if you try hard enough and you don’t care about proving it scientifically.

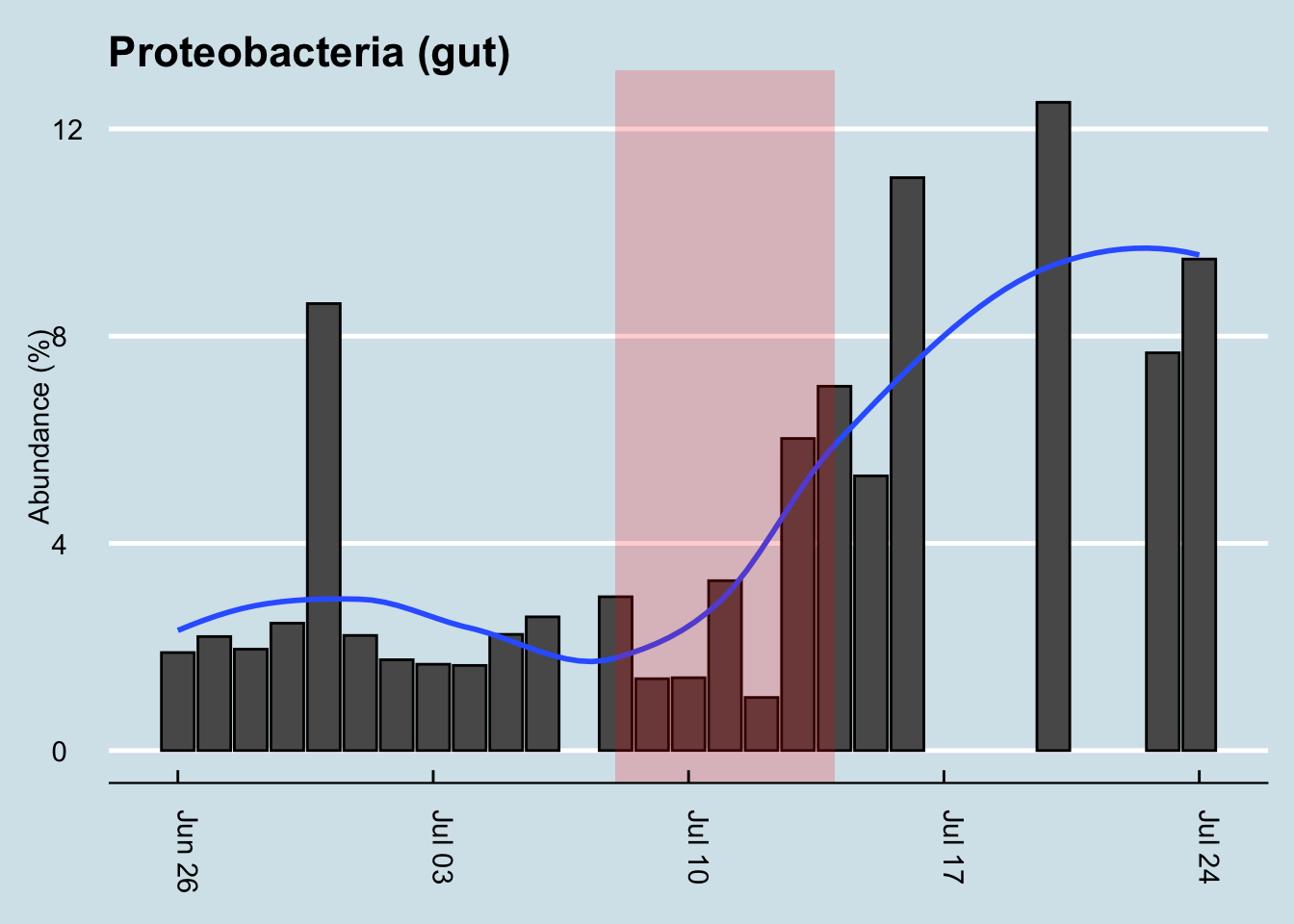

Travel is often good for Proteobacteria, another large family of microbes that changed on this trip. Whenever I see high levels, in myself or others, I usually find that the body is undergoing some kind of challenge – often as a result of exposure to something unhealthy, like a sick person or bad food, and sometimes accompanied by symptoms like an upset stomach or fever. Are the symptoms a result of the higher levels of Proteobacteria or a cause? Maybe this phylum contains plain old pathogens, which would explain the rise in abundance, or maybe – and I’m speculating – it rises as a natural defense to protect us against?

Look how my levels rose 3.11. Shortly after returning home, I was on another plane, for a week in the Midwest. All that travel appears to have kept my Proteobacteria levels high. (Unfortunately I’m missing a few samples during that period, but I think you can see the trends). I was never ill during my trip – at least not with symptoms I could feel – but my previous bouts of illness almost always coincide with a bump in Proteobacteria, so who knows.

Figure 3.11: Gut Proteobacteria abundances rose during a period of heavy travel. Note: zero abundances are days with no samples available.

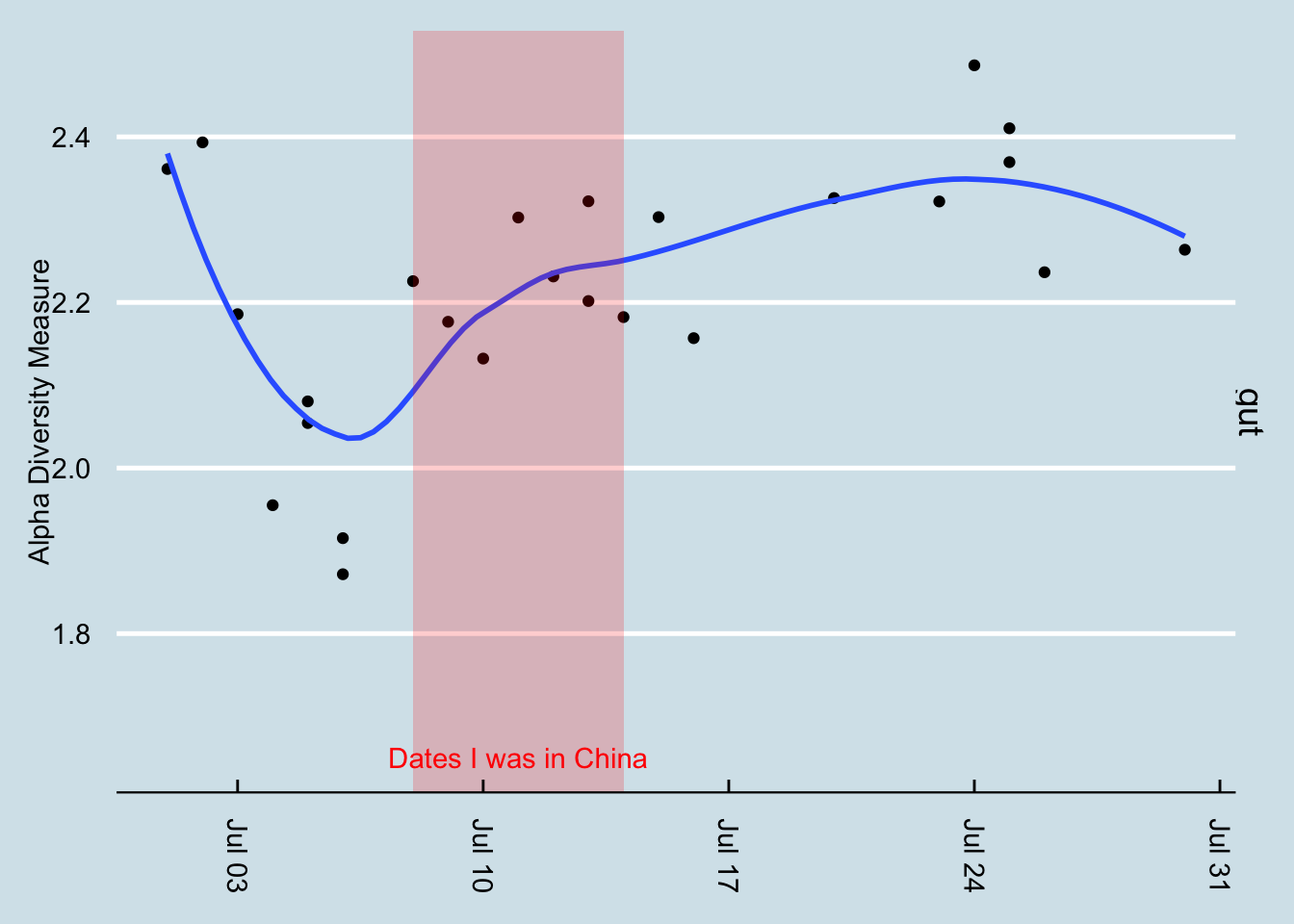

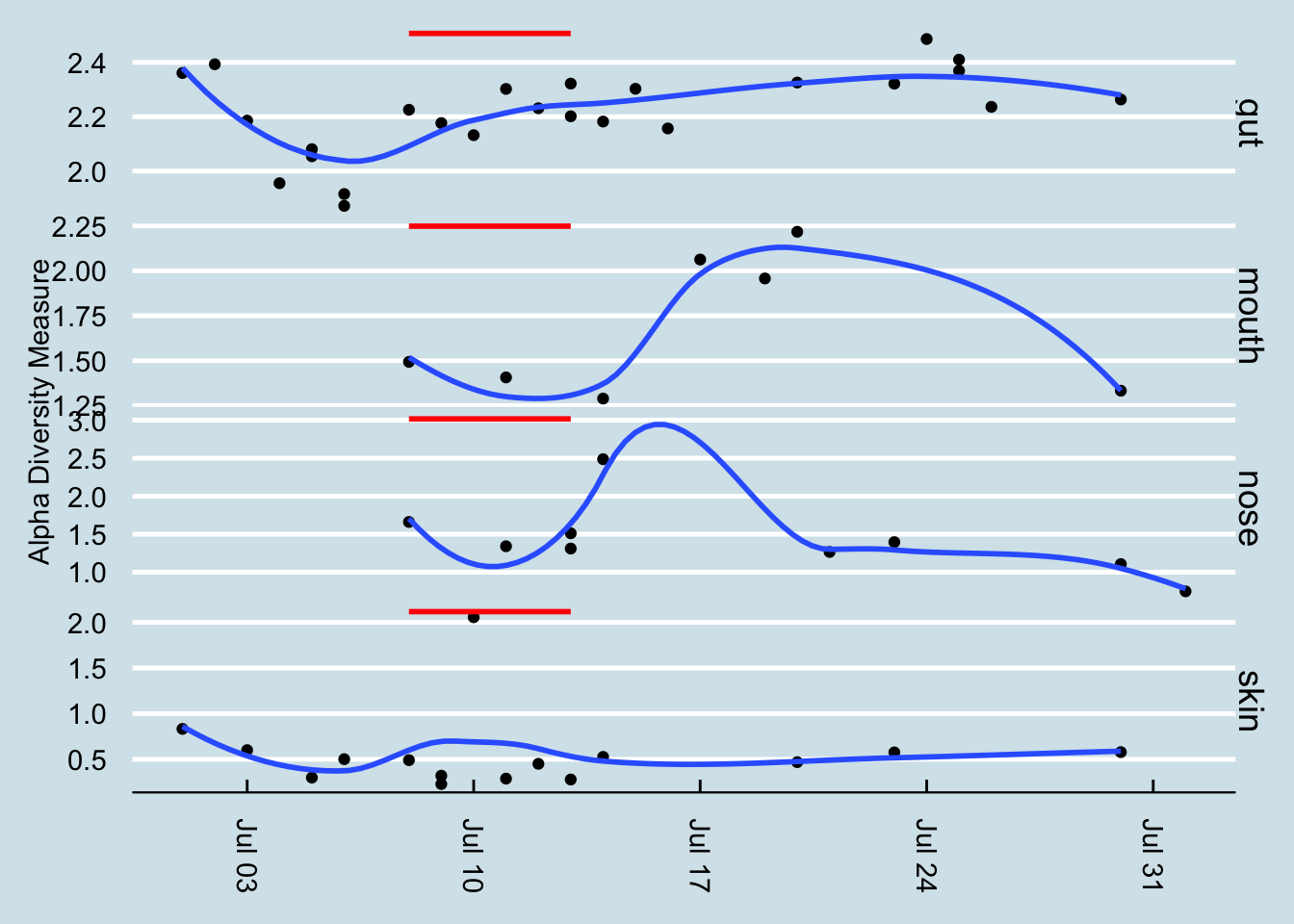

How about diversity? Did that change? (Figure 3.12)

Figure 3.12: Shannon diversity of gut samples during a week-long trip to Beijing.

Figure 3.13: Shannon diversity of all samples during a week-long trip to Beijing.

Answer: maybe. As always, my diversity seems to bounce up and down for no apparent reason. It’s not surprising that exposure to an all-new environment might tend to bring out new microbes too, as in the case of Coprobacter. In this case, at least as measured at the family taxonomic rank, there was a slight shift upward in diversity. Incidentally, on the dates after the red line, I stopped at home for a day or two and then continued on to another part of the United States. That’s a lot of travel, so it wouldn’t be surprising for it to have an effect on my microbial diversity.

It was a similar story with the diversity of my mouth, nose, and skin: if I really wanted to imagine that a visit to China caused a change in diversity, I could point to a few samples that seem to make the case, but inevitably diversity shifted again soon afterwards with no apparent cause.

I could find no other clear pattern of change in any of the other sites. When I looked through each of the individual taxa, none of them

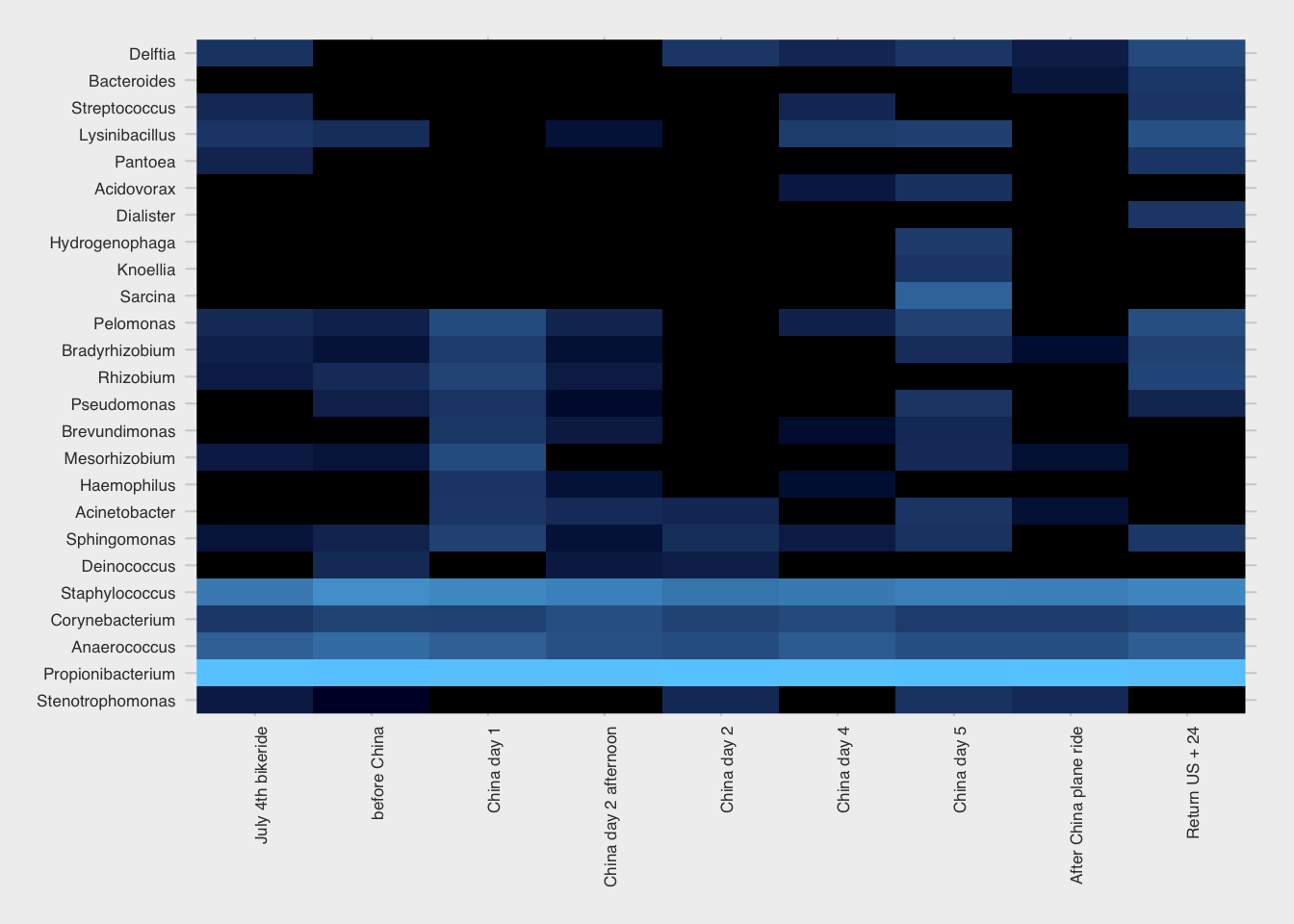

Let’s look at the other sites I tested. Did anything unusual happen in my skin microbiome? As usual, I look first at the overall heatmap to spot any obvious changes.

Figure 3.14: Heat map of my skin microbiome before and after a trip to China.

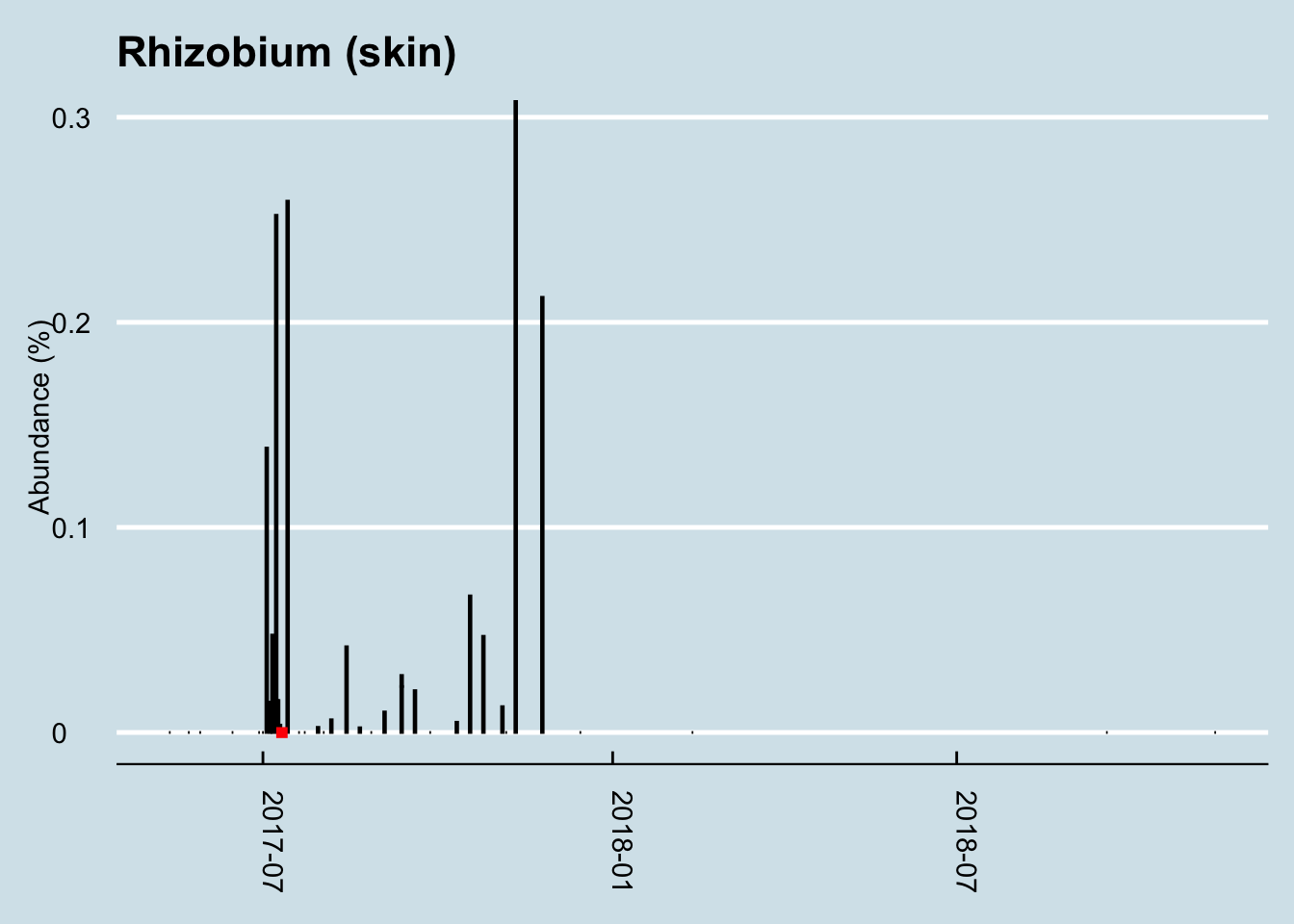

One of these, Rhizobium is fairly abundant during the week or two before my trip, but then seems to disappear a few days after my arrival, only to bloom again right afterwards. Interestingly, Rhizobium is a important nitrogen-fixing microbe found in soil, always near a plant host. What might that have to do with China, or with international plane travel? I looked more closely at the abundance of this microbe over time and found that it appeared in my skin only once before, during an extended visit to the northeastern U.S. Like the China trip, it happened over the summer when I typically spend more time outdoors and have greater contact with the soil. Another spike happened right after a camping trip, which makes sense.

The change in Rhizobium abundance this time was indeed unusual, because it seems to not have been related to anything unusual on my part. It was nice weather and I went hiking a few times during that period, but there were many other times I went hiking that didn’t see a bloom in this microbe.

Figure 3.15: Long-term abundance of Rhizobium in my skin microbiome. Red line indicates the period of traveling to China.

My conclusion: international travel to a very different place, like China, causes some changes to the microbiome, as you would expect. There is at least one gut microbe, Coprobacter, whose bloom seems highly correlated to this particular trip. I could find no other major changes that could be pin-pointed to travel this way, although the extensive testing I did for this experiment let me notice another microbe, Rhizobium whose unexpected rise seems to have occured just before the trip and continued to show up now and then afterwards.