3.10 Kombucha

For healthy bacteria-rich drinks that affect the microbiome, many people immediately think of kombucha. Served chilled during the summer, it has a well-deserved reputation as a natural refreshing alternative to soft drinks. Despite its tangy, mildly sweet taste, it has a surprisingly low amount of sugar: only six grams in a serving100, compared to more than 20 grams in the same amount of orange juice or 39 grams in a can of Coke.

The sugar is missing because it’s been eaten by microbes, a complex blend of bacteria and yeast that convert regular tea (usually black, but also oolong or green tea) into a complex, flavorful beverage. The fermentation process is ideal for adding other ingredients for taste, so there is no end to the interesting flavors possible, giving rise to a highly competitive commercial market: U.S. supermarkets sold $180 Million of the drinks in 2015.

Kombucha fermentation begins with a SCOBY, a “Symbiotic Colony of Bacteria and Yeast”, a pancake-sized disk-shaped gelitintous object also known as a “mother” or “mushroom”, which it sort of resembles. Despite the nickname, the only funji in the SCOBY are yeasts, combined with a complex blend of bacteria and other single-celled microbes from many parts of the tree of life. The different microbes need one another to produce the distinctive sweet and fizzy taste. Yeast cells convert sucrose into fructose and glucose and produce ethanol; the bacteria convert glucose into gluconic acid and fructose into acetic acid; caffeine from the tea stimulates the entire reaction, especially the production of cellulose by special strains of bacteria.101

There have been many anecdotal claims of the effect of kombucha on health, purporting benefits ranging from better eyesight and thicker hair to cures for various diseases, though not everyone thinks it’s healthy. Even some alternative health experts, like Dr. Andrew Weil, recommend against it. Many of the claims for and against kombucha have been studied experimentally, in mice as well as humans, often with compelling results, but I’m unable to find any good data showing how it affects the microbiome.

So I tested it myself.

For seven days, from July 27 to August 2, I drank 48 ounces per day of commercially-purchased GT’s Gingerade Kombucha. That’s three full bottles, or six servings a day for a week.

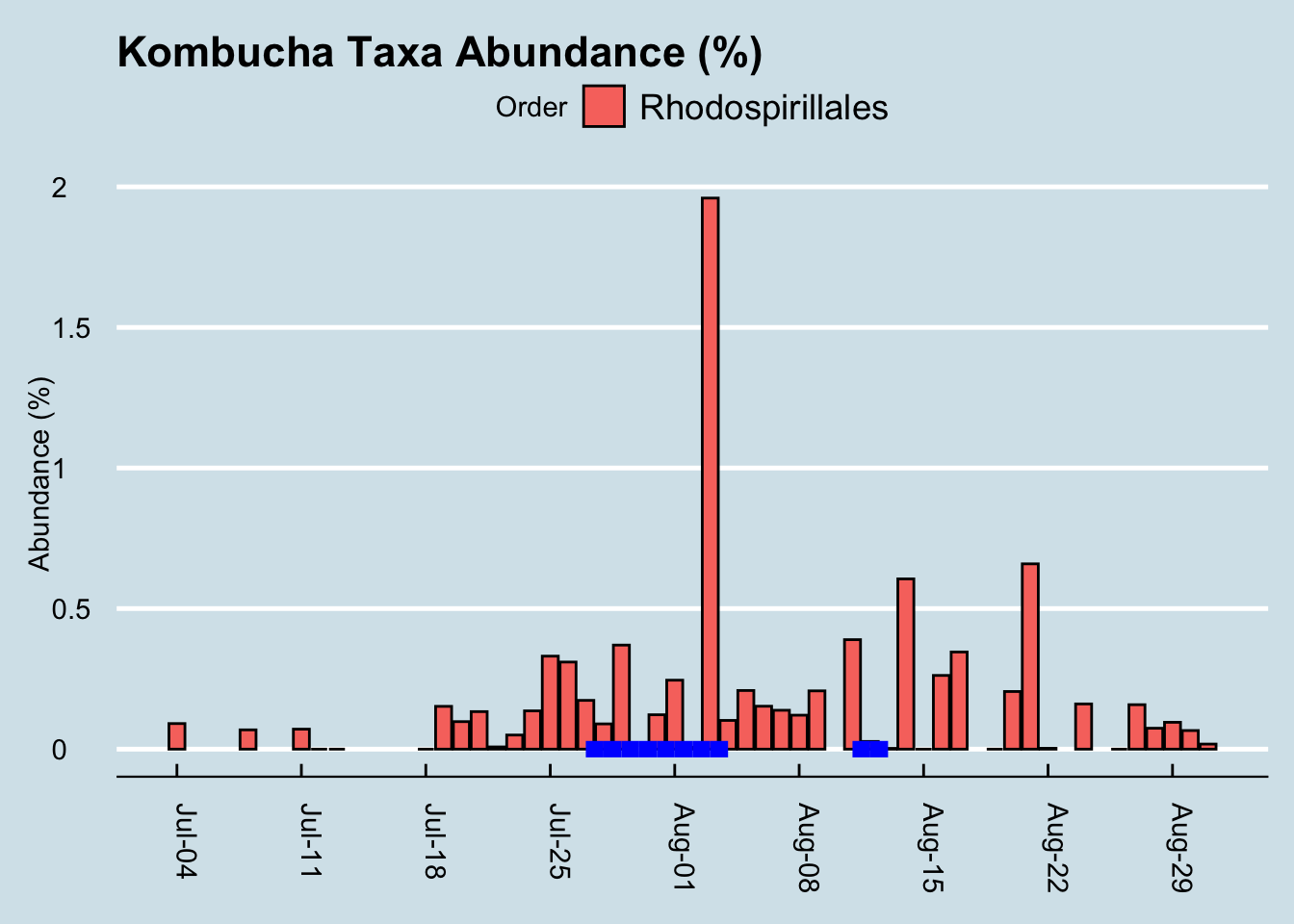

The key bacteria in the SCOBY are from phylum Proteobacteria and order Rhodospirillales of acetic- and gluconic-acid producting microbes that include genus Gluconacetobacter, closely related to Acetobacter, the key to the fermentation of vinegar. Thanks to the action of these microbes, kombucha is quite acidic, between 2.5 and 3.5 pH, almost as acidic as the 1.5 or 2.5 of a healthy stomach. These bacteria apparently don’t survive ingestion. They are rarely, if ever, found in human guts102, so whatever effect, if any, they have on the microbiome is indirect.

The label claims each bottle contains one billion organisms of two microbial species. The first, Saccharomyces boulardii, is a popular “healthy” microbe, well-studied and proven as a safe digestion aid. A close cousin of brewer’s yeast, its cell wall tends to stick to pathogens, which may account for its proven ability to prevent and fight diarrhea.103. Unfortunately, it is not a bacterium, and so won’t be detectable in my 16S-based microbiome tests.

The other added species Bacillus coagulans is often found in human guts, and should be easy to find. The specific one used in GT’s drinks is the patented Bacillus coagulans GBI-30, 6086, a particularly hardy spore-forming microbe that can survive boiling and baking. Because it’s well-studied and safe, it’s a popular “probiotic” food additive and appears to have some beneficial effects on digestion.104

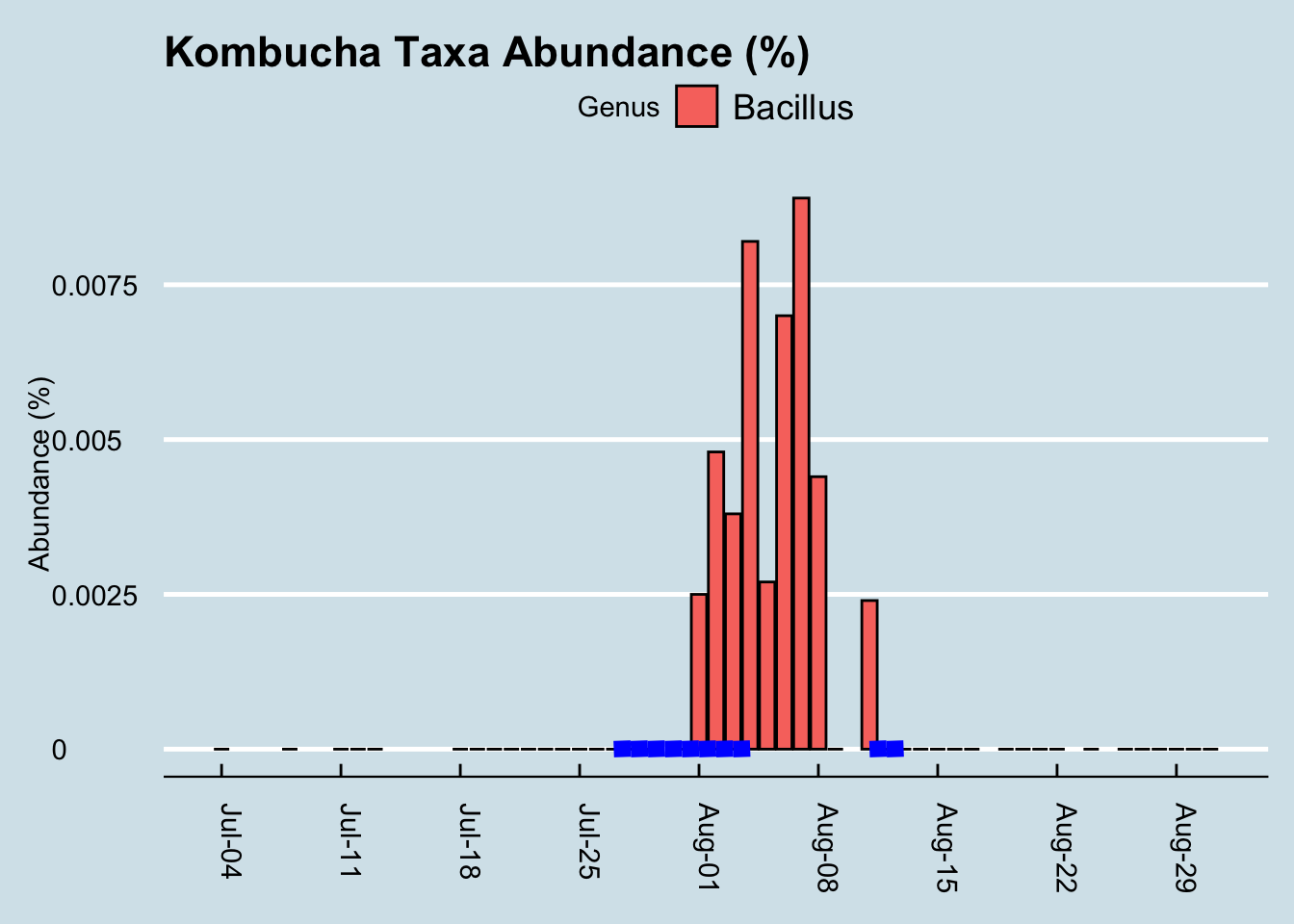

I tested my gut microbiome each day, as well as my mouth and skin microbiome at intervals during the experiment and sure enough, the Bacillus shows up loud and clear. (Figure 3.25 )

Figure 3.25: The blue line represents days I drank 6 servings of kombucha.

It took a few days of heavy kombucha drinking, but eventually those microbes became detectable. Given the known hardiness of Bacillus, this isn’t necessarily all that surprising. Still, it’s a nice confirmation that the test works; after all, in my hundreds of daily tests, I see this microbe only in the few days after drinking this brand of kombucha. But maybe the Bacillus just comes in and out, safely protected as a spore, without really influencing my microbiome. Can we see evidence the kombucha affected something else about my microbiome?

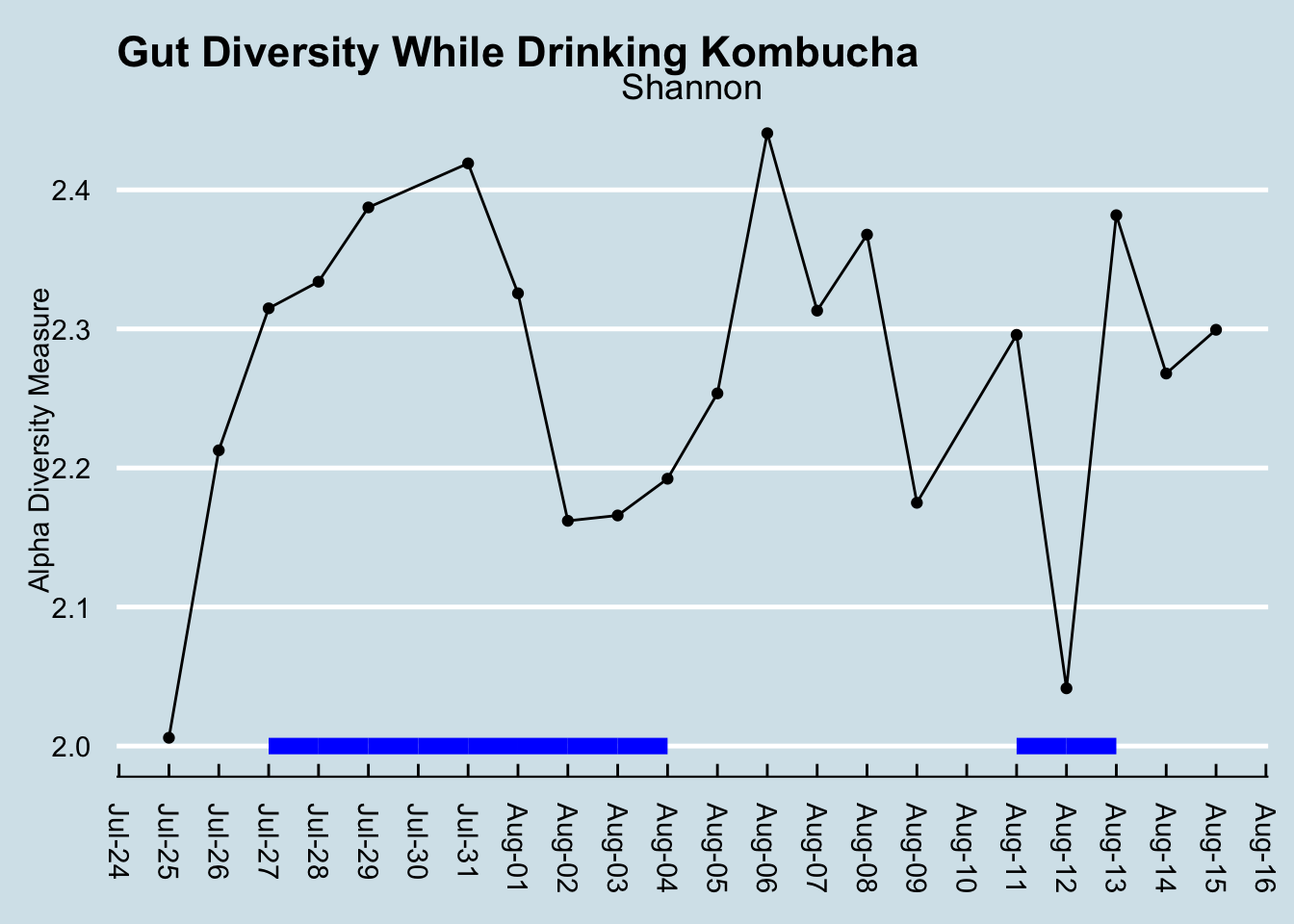

Diversity doesn’t seem to change (Figure 3.26). I looked at the overall mixture of microbes and abundances using the Shannon diversity metric, commonly used by ecologists to tell measure the richness and variety in an environment. Don’t let the scale of this graph fool you: I set it narrowly to see precisely how diversity changes each day. A Shannon diversity change of a tenth of a point or so, as in this graph, is pretty trivial.

Figure 3.26: How my overall family-level diversity changes while drinking kombucha. I drank 6 full servings on each of the days marked with the blue line.

Diversity had been climbing before the experiment began, so I don’t think we can lay that initial increase on kombucha. Incidentally, had I not been testing daily, I might be tempted to say diversity decreased. This is something that makes me skeptical of the results of many scientific studies: the microbiome flucutates so much day-to-day that what you see is very dependent on when you test. (By the way, note that the July 30 sample is missing, due to a failure in the lab processing.)

Let’s look at that order Rhodospirillales that contains the genus Acetobacter found in the SCOBY. (Figure 3.27)

Figure 3.27: Abundance of microbes that include the genus Acetobacter found in the SCOBY

If we squint enough, we might credit that large spike with kombucha drinking. It’s possible, but then how would you explain the crash the following day, or the other apparent spikes in other parts of the chart? I conclude it’s probably a coincidence. More than likely, microbes like this from the SCOBY itself are not in the beverage anyway.

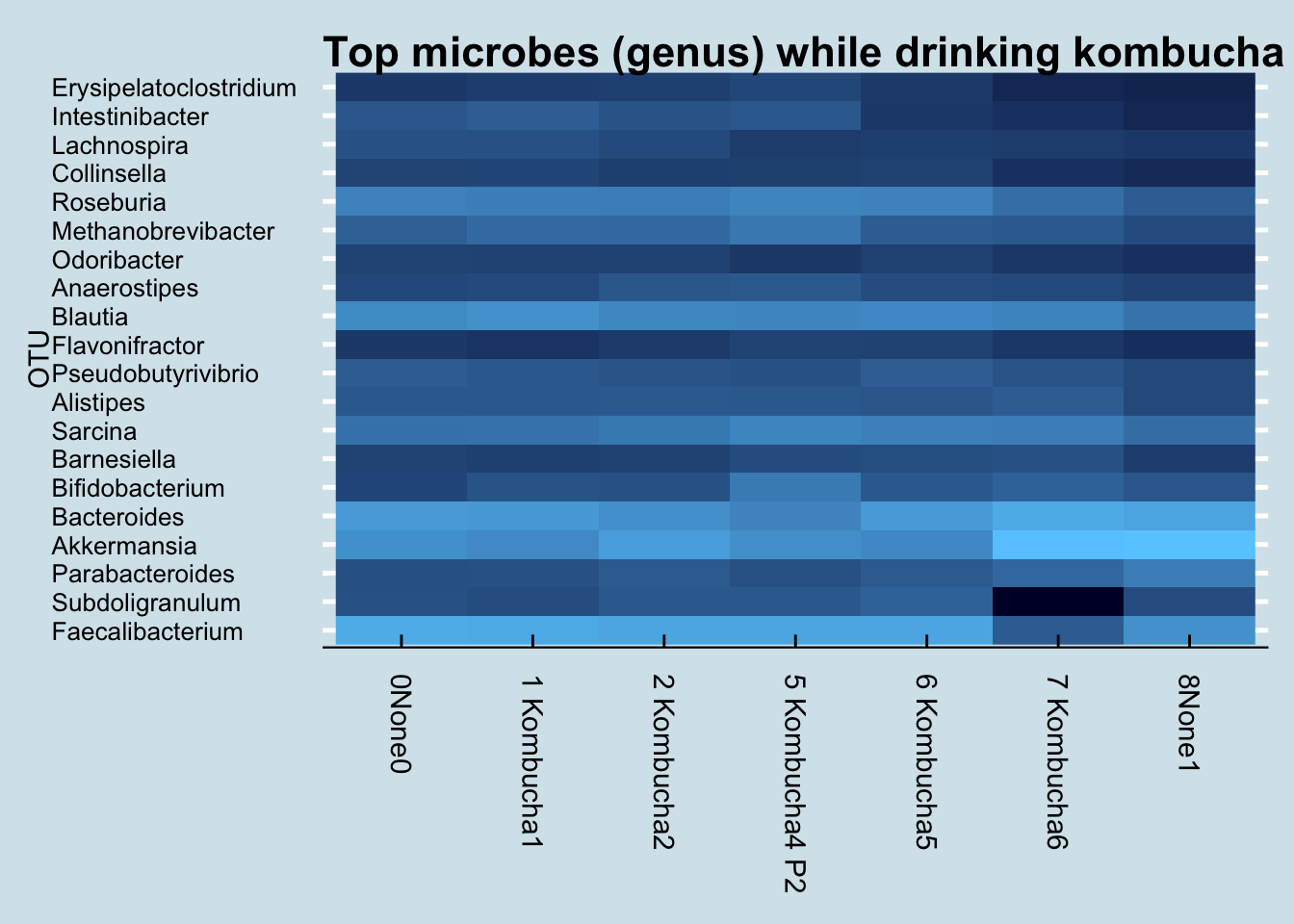

What about other microbes? Here is a heatmap showing the changes of the top 20 genus during my experiment:

I don’t see any patterns. Usually, if the experiment causes a change, I’ll see an obvious streak from left to right somewhere in the heatmap, but I don’t see that.

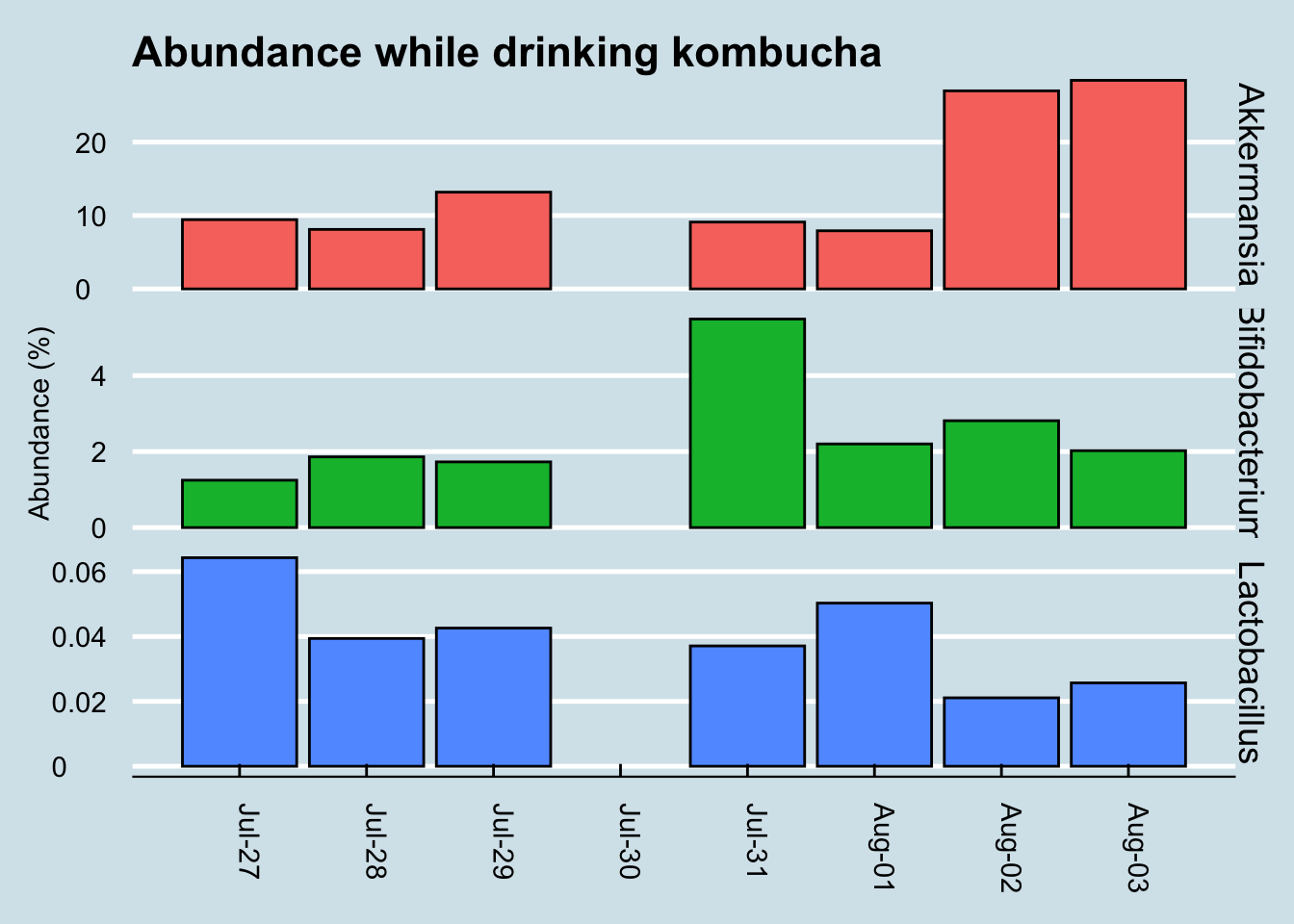

Finally, let’s look at the levels of a few “probiotic” microbes, including the one listed on the label (Figure 3.28)

Figure 3.28: Abundance of key ‘probiotic’ microbes while consuming kombucha.

While Akkermansia seems to rise near the end of the sequence, it’s hard to see any real patterns here.

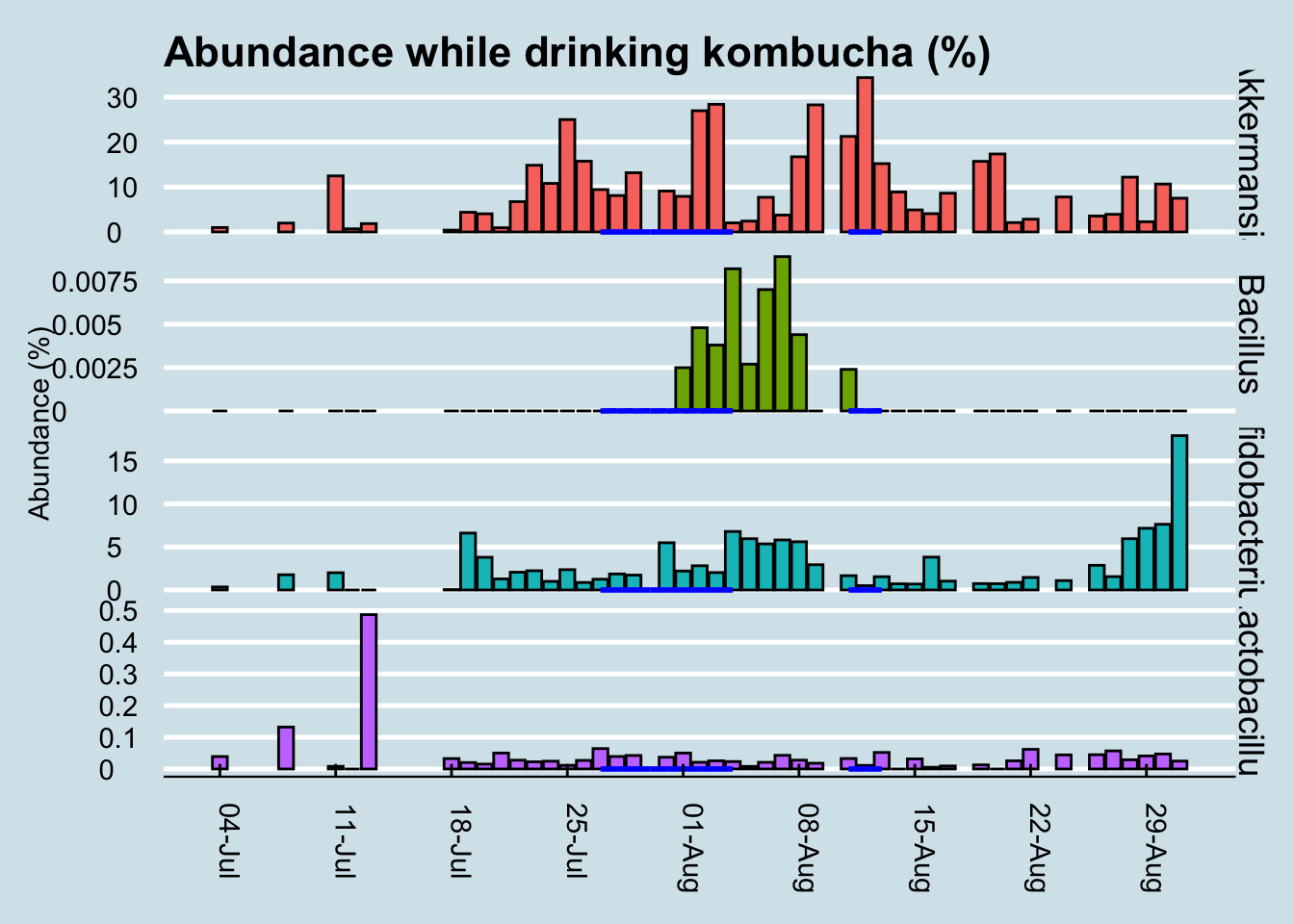

For comparison, let’s look at a longer time horizon (Figure 3.29)

Figure 3.29: Daily abundance of key microbes while drinking kombucha (blue lines). Blank regions are days when I have no data.

Although we can’t positively credit kombucha for that spike in Bacillus during my experiment, it’s interesting that I had none of it in the weeks beforehand, and that it disappeared again in the weeks afterwards. I drink this brand of kombucha occasionally, and yes the same microbe shows up occasionally too, sometimes a few days afterwards.

In my years of testing, I rarely see Bacillus in my gut microbiome, but the few times when it does appear, there seems to be a relationship to drinking the same brand of kombucha a few days beforehand. There are also times when I drink kombucha and don’t detect this microbe, so the association isn’t perfect, but then again this was the only time I had so much of this brand all at once.

My conclusion: when consumed in large amounts, GT’s Gingerade Kombucha leaves new Bacillus microbes in my gut. Although they don’t appear to stick around permanently, the association is strong enough that I bet it works in you too. Other microbes, including so-called “probiotic” ones, don’t change much at all.

But don’t take my word for it. The full dataset and analysis tools are on Github: https://github.com/richardsprague/kombucha

There is much more analysis that can be done with this data. Some of the ideas you might try are:

- Study correlations among the taxa. Which ones are correlated, and which are not?

- Which taxa appeared and/or disappeared during the experiment?

- Is there a relationship between the microbes known to be present in kombucha and those in any of the gut results?

- How do these results compare to you when you drink kombucha?

Please study as much as you like, and let me know what you find!

P.S. The term “kombucha” is an unfortunate mistranslation of a Japanese word (昆布茶) that means “seaweed tea”. A fermented version of seaweed tea exists, but it has nothing to do with the drink described here.