3.2 Kefir and the Microbiome

Everyone interested in the microbiome eventually has to check out kefir. Google the phrase “one of the most potent probiotic foods available” and you’ll find kefir in all the top results. A recent BBC documentary that tested people after consuming different types of “gut-friendly” foods found it had by far the biggest effect. My interest piqued when, after my disappointment with kombucha, I spoke with a man who happened to mention his good luck with kefir as a solution to his many gut issues. On a doctor’s recommendation, he tried kefir for a number of years with limited success, until — frustrated with the $3/day expense of buying it at Trader Joe’s — he began making it himself at home. “What a difference!” he claimed.

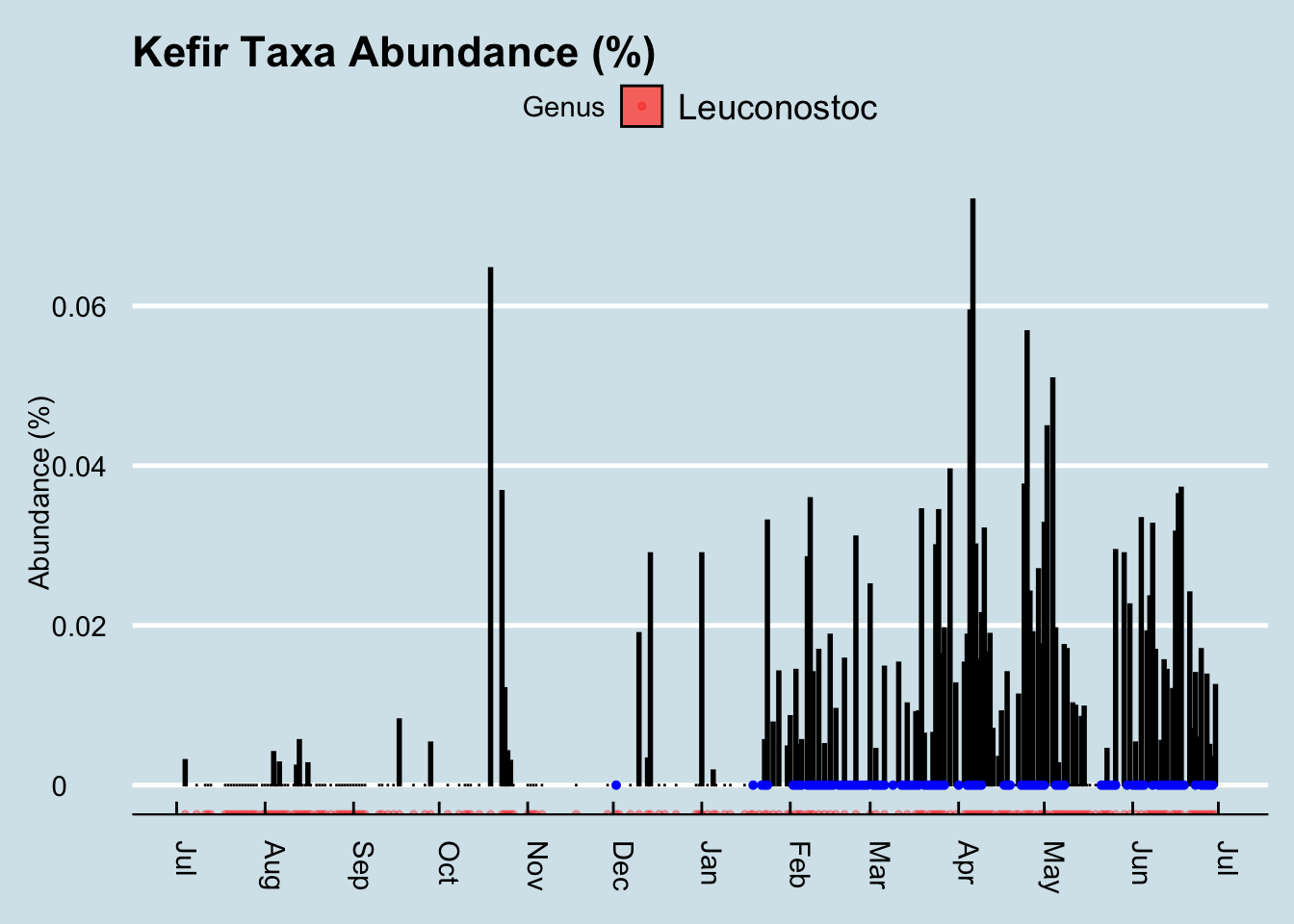

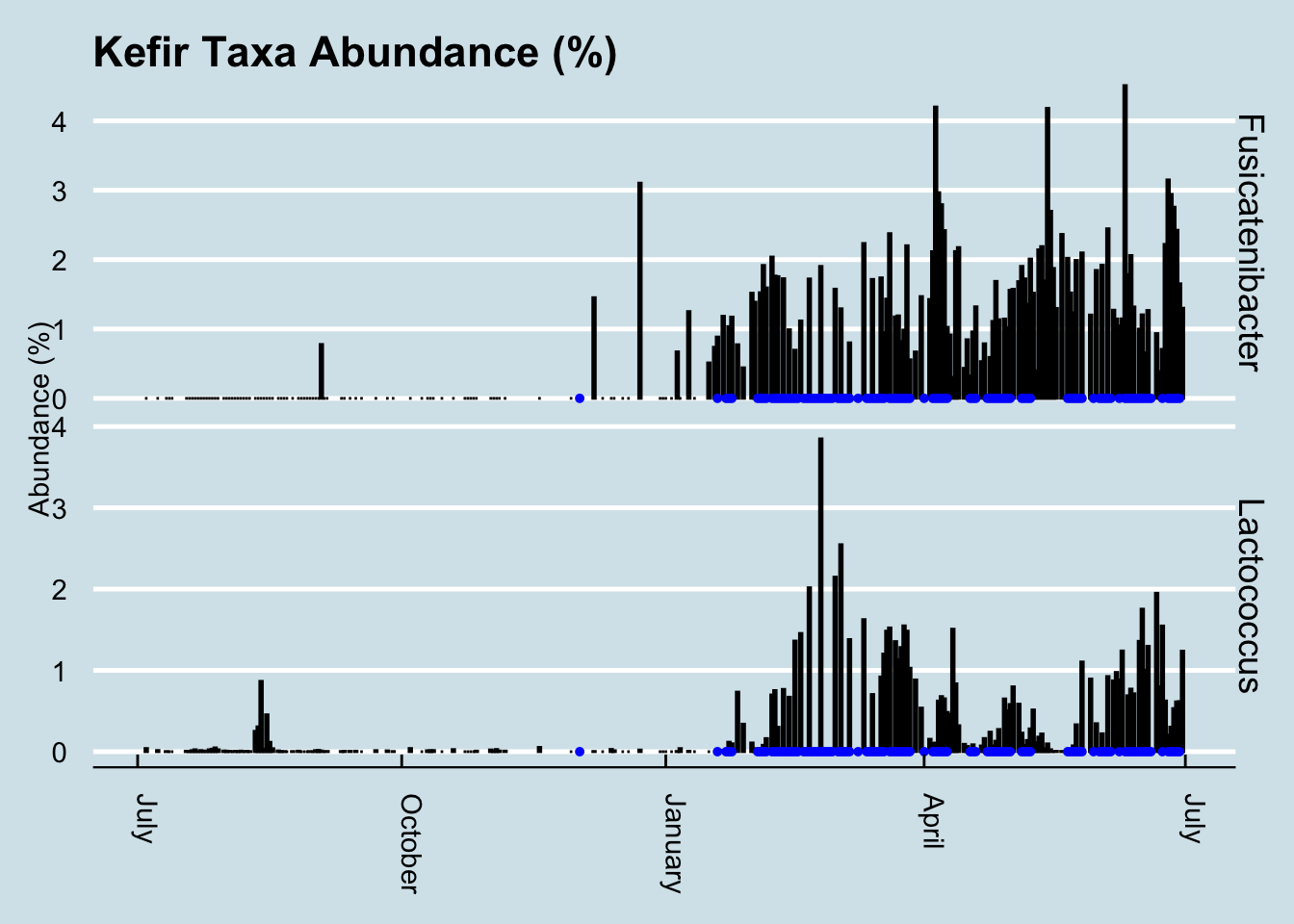

Did it work for me? Yes! I found a very noticeable change in my gut microbiome — the most significant I’ve seen among my many experiments. Look at my daily levels of Leuconostoc, a prodigious synthesizer of Vitamin K known to be found in kefir. (Figure 3.5 )

Figure 3.5: Levels of this key microbe jump suddenly when I drink kefir (blue dots)

The blue dots in the chart are days when I drank kefir. Since I sample near-daily over the entire chart, we can see that both of these taxa suddenly appeared shortly after I began to consume kefir. I had almost none beforehand. Also note that the levels seem to dip when I skip drinking for a few days, such as during my business trips out of town in mid-March and another in early-April.

So apparently it has a big effect on the microbiome. What is this stuff anyway?

The first thing to know about kefir is the pronunciation. Say “Keh-FEAR”, with the accent on the second syllable, not “KEE-fur” or “kEH-fir”. The Russian origin of the term is a reminder of a time in the distant past when — it’s unclear exactly where or how — the first batch was prepared and then passed along, its microbial components shared from person to person until it reached today’s status as a popular drink you can buy in most grocery stores.

Making it at home brings more than just financial benefits. Commercially-purchased drinks are subject to unavoidable regulatory, shelf-life, and consistency contraints that matter for successful business, but not necessarily for nutrition. More importantly, if you believe like I do that microbes are highly-customized to our environments, making at home will ensure that the kefir is well-adapted to your own personal microbial environment. The batch that survives and thrives in your kitchen will have proven its ability to withstand whatever conditions you face there.

Making it yourself is surprisingly easy. It begins with a bundle of the component microbes, a cauliflower-shaped substance usually called the “grain” or “seed” that looks like this:

Instruction books often tell you to be careful how you handle the grains, but I find them robust enough that I pick them up with my bare fingers. I drop them into a glass of milk left I leave sitting on the counter overnight and — voila! — twenty four hours later, the liquid has turned into kefir. Pull out the kefir grains from that glass, plop it into another, and you’re all set for tomorrow’s batch. Unlike yogurt, which requires heating and a stable temperature, kefir doesn’t appear to care how it’s handled, so long as you keep it at room temperature and can wait for twenty four hours. The reaction might vary by a few hours if the room is a bit colder or warmer, but otherwise I find it surprisingly consistent. Just set and forget.

I found that the only hard part is getting started. Once you have the grains, making more kefir is easy, but where do you get the grains in the first place? It’s supposedly possible to make them from scratch using a goat-hide bag filled with pasteurized milk and the intestinal flora of a sheep, but I haven’t tried that myself. I’m told it works so long as you shake every hour and maintain a constant temperature.

You can order some starter grains online for under $25, but for shipping purposes the manufacturers generally give them to you in a freeze-dried form that requires a week or so of preparation before the microbes are fully alive and kicking out drinkable quantities of kefir.

I got mine by asking around until I found a neighbor who had been brewing his own. Anyone who makes homemade kefir will be happy to give you some extra grains. The fermentation process causes the grains to multiply, and you will find yourself throwing them out regularly.

The grains themselves contain a combination of lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Leuconostoc), acetic acid bacteria (Acetobacter), and yeast, clumped together with casein (milk proteins) and complex sugars in a type of carbohydrate molecule called kefiran. The nutritional content apparently varies depending on fermentation time and other factors, but there’s a lot of good stuff in there86 (Figure 3.6).

![Nutritional content of kefir. [Source: @otles_kefir_2003]](Experiments/assets/kefir-oltes-nutrition.jpg)

Figure 3.6: Nutritional content of kefir. (Source: Otles and Otles 2003)

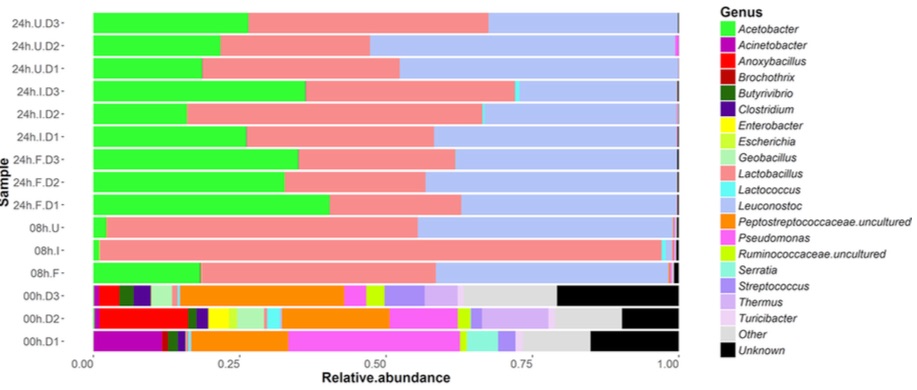

A rigorous microbial analysis by an Irish lab 87 recently showed precisely which microbes are present in kefir, at various stages in the fermentation process. This chart shows the composition of ordinary pasteurized milk as it changes from before adding kefir grains (time 0 at the bottom) until 24 hours have passed (top) and the milk has been transformed into just Acetobacter, Lactobacillus, and Leuconostoc.

The uBiome test I used unfortunately can’t detect yeasts, so I don’t have an easy way to track the non-bacterial microbes in my kefir. But I can run the mixture through the same gene sequencing that I use for my other samples. I tested the kefir twice: once by simply dabbing the swab into the mixture that was waiting for me in the morning, and another swab from the same batch after removing the grain for an additional 24-hour “second ferment”. This is what I found when I sequenced the kefir from two different batches: (Table 3.1)

| Kefir1 | Kefir2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Lactococcus | 96.06 | 1.07 |

| Leuconostoc | 3.02 | 0.06 |

| Lactobacillus | 0.22 | 98.40 |

| Faecalibacterium | 0.14 | 0.01 |

| Roseburia | 0.06 | 0.00 |

These are the only taxa that met the 0.07% abundance criteria discussed previously. But even without that cutoff, the uBiome pipeline shows no Acetobacter, despite its prominence in the study shown above.

I wondered if this is simply due to the way uBiome labels the taxa that are found. Maybe the label Acetobacter just isn’t often assigned to uBiome samples. When I checked, I could find none in any of my own samples or of the hundreds of others that people have sent me. What’s more, none was reported in a large population study88 either. So apparently it just doesn’t show up often in humans, though I wonder why it wouldn’t show up in the 16S sequencing of my kefir sample.

The answer, according to the uBiome scientist I talked to, is that Acetobacter is too similar to other genera for it to be accurately distinguished with a 16S test. So if we can’t see at the genus level, let’s look at a higher level, such as phylum. (Table 3.2)

| Kefir1 | Kefir2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Firmicutes | 99.75 | 99.57 |

| Bacteroidetes | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| Proteobacteria | 0.09 | 0.36 |

| Actinobacteria | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Verrucomicrobia | 0.01 | 0.00 |

Because Acetobacter is within Phylum Proteobacteria and Order Rhodospirillales, we would expect to see some of those microbes if any of it were present. Looks like my kefir doesn’t include anything remotely resembling Acetobacter.

That’s what’s in the kefir grain itself. How does regular drinking affect my gut microbiome?

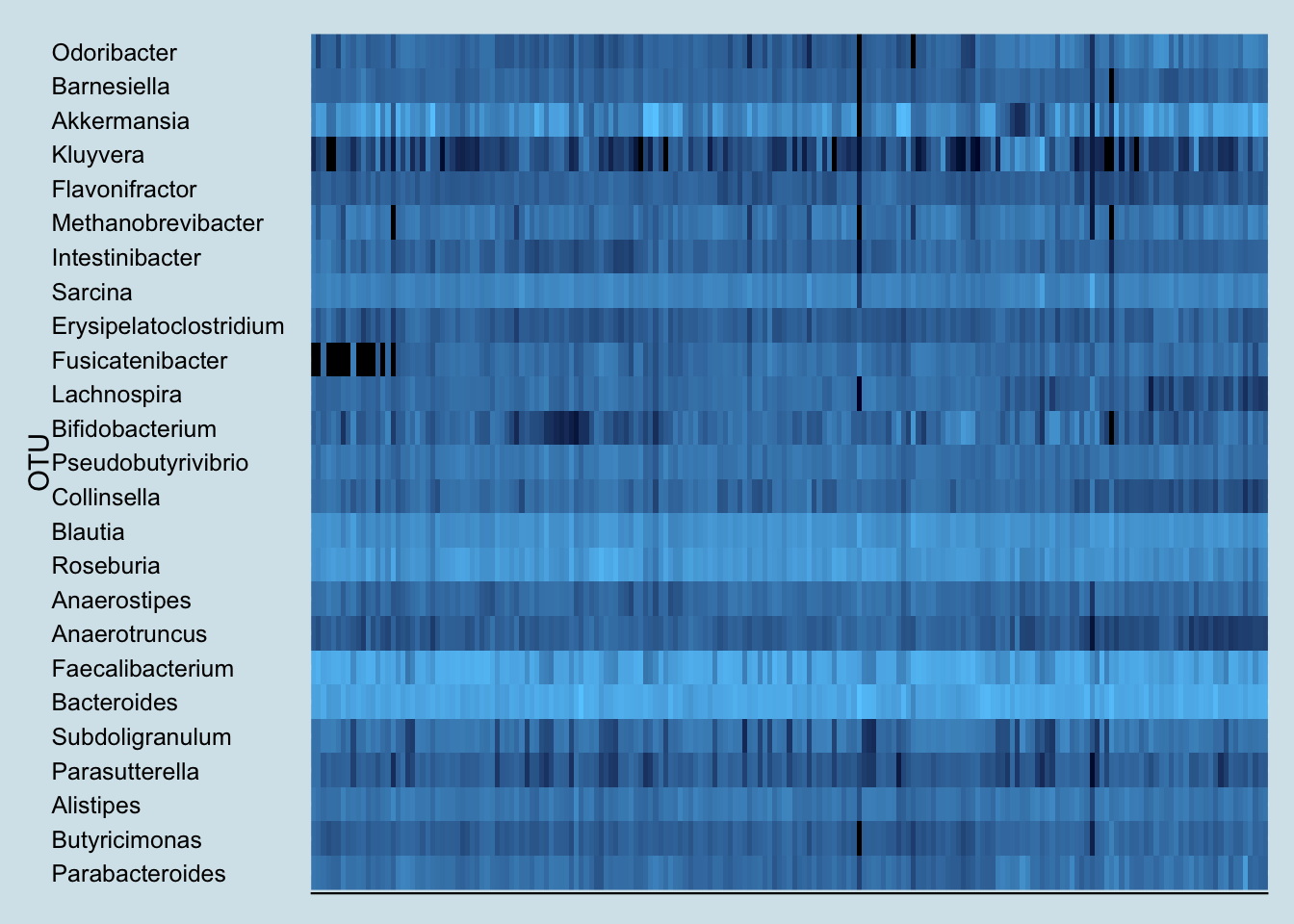

To find any taxa that may have suddenly changed as a result of kefir-drinking, let’s look at a heatplot that shows the relative abundances of all my top microbes over time. Darker spots are days when I have less of a particular bacterium, lighter spots are days when I have more.

Note the sudden appearance of the genus Fusicatenibacter. You rarely see such a dramatic and consistent change as a result of an experiment, but unfortunately, little is known about this genus. A member of the Clostria class of phylum Firmicutes, an internet search reveals little of interest. But it definitely appears in my samples after drinking kefir.

In fact, look how the levels appear to coincide precisely with the periods when I drink kefir:

This is especially interesting because the only previous date when my gut saw any of this taxa was in December – on another occasion when I drank some kefir. In fact, Fusicatenibacter is such a strong predictor of kefir drinking that I can use it as a way to look back in time to see the samples when I drank some.

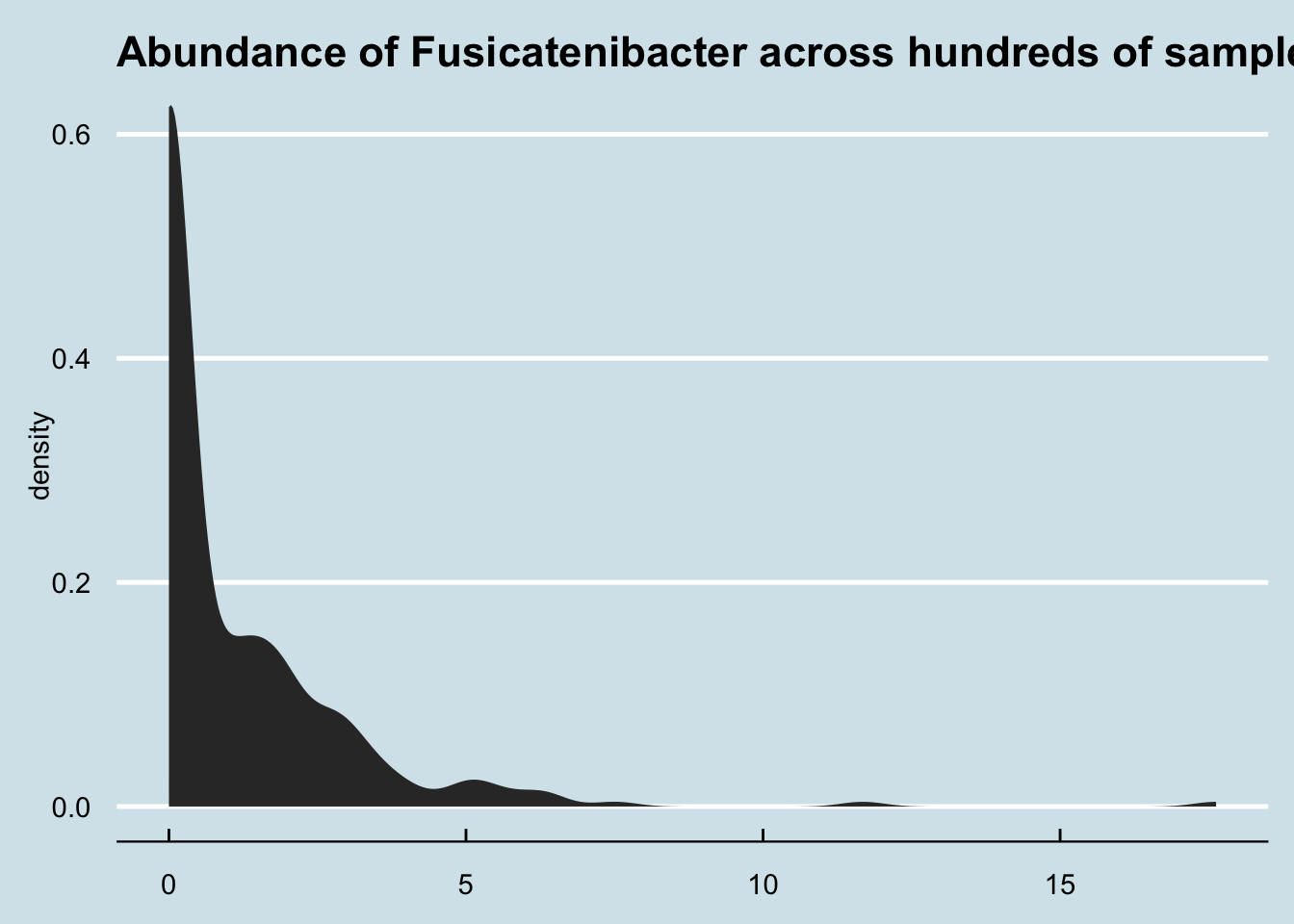

How common is Fusicatenibacter in gut microbiomes? Here’s a density plot look at a few hundred samples collected from other people.

Although most people have none, it’s not unusual for people to have a few percentage points of Fusicatenibacter regardless of whether they regularly drink kefir.

But other than this clear change in my gut microbiome, did I notice any differences in health?

Here the answer is more ambiguous. As a healthy adult, I don’t have any particular “problems” I’m trying to solve. I remained healthy during the period of the experiment, so the kefir certainly doesn’t appear to have made anything worse. My sleep hasn’t substantially changed either, and although I’m generally pretty even-tempered, I didn’t notice any particular changes positive or negative in my mood either.

The one area where, subjectively, where I feel different is in my overall sense of energy. Although I can’t put my finger on anything quantitative, I do notice that I seem to be a little more energetic on days when I drink kefir. Measuring that more precisely may be a good followup test.