4.4 Colorectal Cancer

Paul was a pretty normal father of two teenagers when he noticed something odd in the bathroom. At first he thought it was something he’d been eating; despite a lifetime of Southern living, he didn’t have as much tolerance for deep-fried cooking as some of his neighbors and the past few weeks had been unusually heavy on the grease. So, he laid off the french fries for a few weeks and it seemed to get better. He had enjoyed a lifetime of perfect health: he was rarely sick, had never been inside a hospital except to visit others, and fully expected to live well into his 80s or 90s like his grandparents.

He wasn’t worried, but a few months later his wife reminded him that his company insurance plan includes a free annual physical, and he thought why not. The doctor didn’t seem worried either, but suggested a few more tests “just in case”, and unfortunately that’s when he got the diagnosis that has been on his mind every day since: Stage IV colorectal cancer that has spread to his liver.

If you or a loved one find yourself in tragic situation like this, your first stop should always be with a medical professional. Paul’s oncologist studied this full-time for years of medical school, has treated tens of thousands of cancer patients for 30 years, and gets paid to stay up-to-date on the latest science while interacting with other professionals like him. So it’s beyond silly and arrogant – not to mention dangerous – to ask the opinion of an untrained amateur like me.

But still. Nobody, not even the most caring and selfless doctor, feels the urgency of the situation more than Paul and his family. They’ll try anything; and who can blame them? The same careful, methodical and well-informed approach that makes the mainstream medical profession more effective over the long term, well, maybe it also makes this doctor just slightly more risk averse. There are treatments that no responsible doctor would consider, but what exactly is a “responsible” treatment when you know that your odds are tragically small? Seriously, what’s there to lose?

Intriguing new discoveries have been made in the past few years about the relationship between cancer and the microbiome, and Paul asked if I know anything based on my years of near-daily sampling and amateur study. Might we find something in his microbiome, something that perhaps his doctor hasn’t thought to consider? Given all that’s known about microbiome-healthy diets, maybe if we found something unusual, some out-of-place microbe, is there a chance we might uncover a new, more effective treatment?

](CaseStudies/images/caseColorectalCancerFusobacterium.jpg)

Figure 4.3: The culprit? Courtesy of Dr. Allen-Vercoe, University of Guelph Katz Lab

Many cancers seem to have a relationship with the microbiome. There are at least ten viruses which are known to be carcinogenic, including Human papillomavirus (HPV) that causes cervical cancer, and for which there is a vaccine. Some scientists guess that most cancers will eventually be shown to have their origins in a microbe, and although that’s mostly speculation at this point, the idea of using microbes to treat or prevent cancer has attracted interest for more than 100 years.

Fusobacterium nucleatum, Bacteroides fragilis, and many members of the large class of Enterobacteriaceae have well-studied characteristics that make them liable to cause the types of genetic damage that can give rise to cancer.

I repeat: I’m not an expert – I have no training or credentials in this at all – so please don’t take any of the following analysis as a substitute for the advice of a trained professional. Over the years, I’ve seen thousands of results from microbiome tests, including hundreds from people who claim to be healthy. We know for certain that Paul’s chances are uncertain – even with the best medical help in the world. Who can blame him for reaching out to anyone else who might have some insights? The obvious place to start is to look at how Paul’s microbiome sample may or may not differ from those healthy users.

Overall, I found his gut diversity is a little on the low side – a Shannon value of 1.2. I’m usually somewhere between 2.0 and 2.5, though it’s not uncommon to see lower, and there’s so much day-to-day variability in gut diversity that I wouldn’t take a single result very seriously.

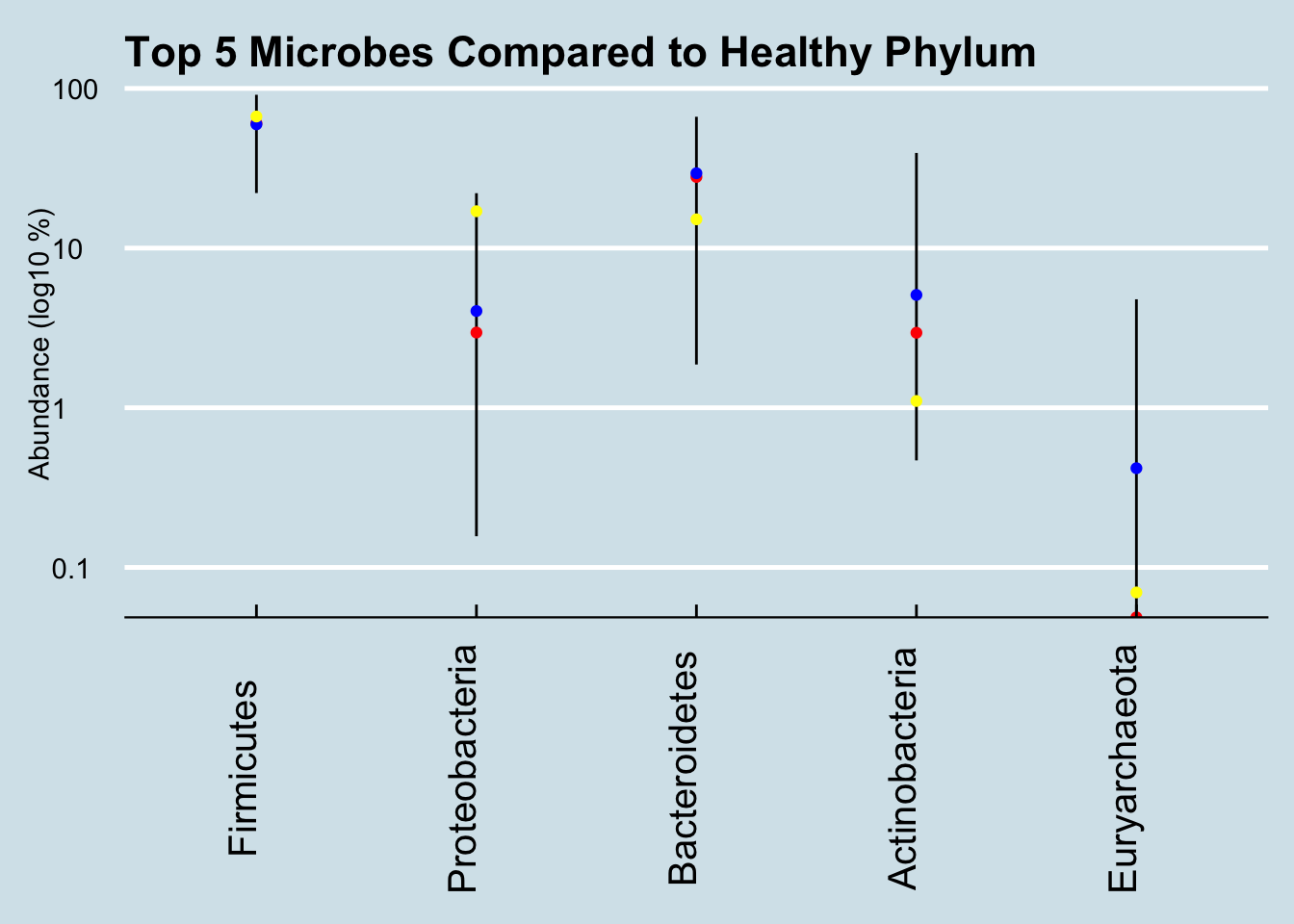

Next I looked at the broadest, Phylum level, where I ranked all the microbes in comparison to the healthy samples, picking out the top ones that seem to be outliers. The following charts show the percentage abundance of Paul’s top microbes (yellow dots), compared to the average (blue dot) and median (red) for my database of healthy people. The vertical lines show the range of abundances I’ve seen in healthy people, so a yellow dot above or below that line is an outlier that’s worth considering further.

Figure 4.4: Healthy ranges compared (Phylum).

That high level of Proteobacteria is a clue that something’s not right. I’ve noticed that this microbe tends to be high in people with gut issues; Kluyvera, E. Coli, Shigella and most common pathogens are in this group. Now, this is only one test, and it’s not uncommon even in healthy people for the levels to show up high now and then. In my daily sampling, I’ve often had several results that high, including one or two at 25% for no apparent reason. Still, maybe it’s worth looking more closely, at the Order level:

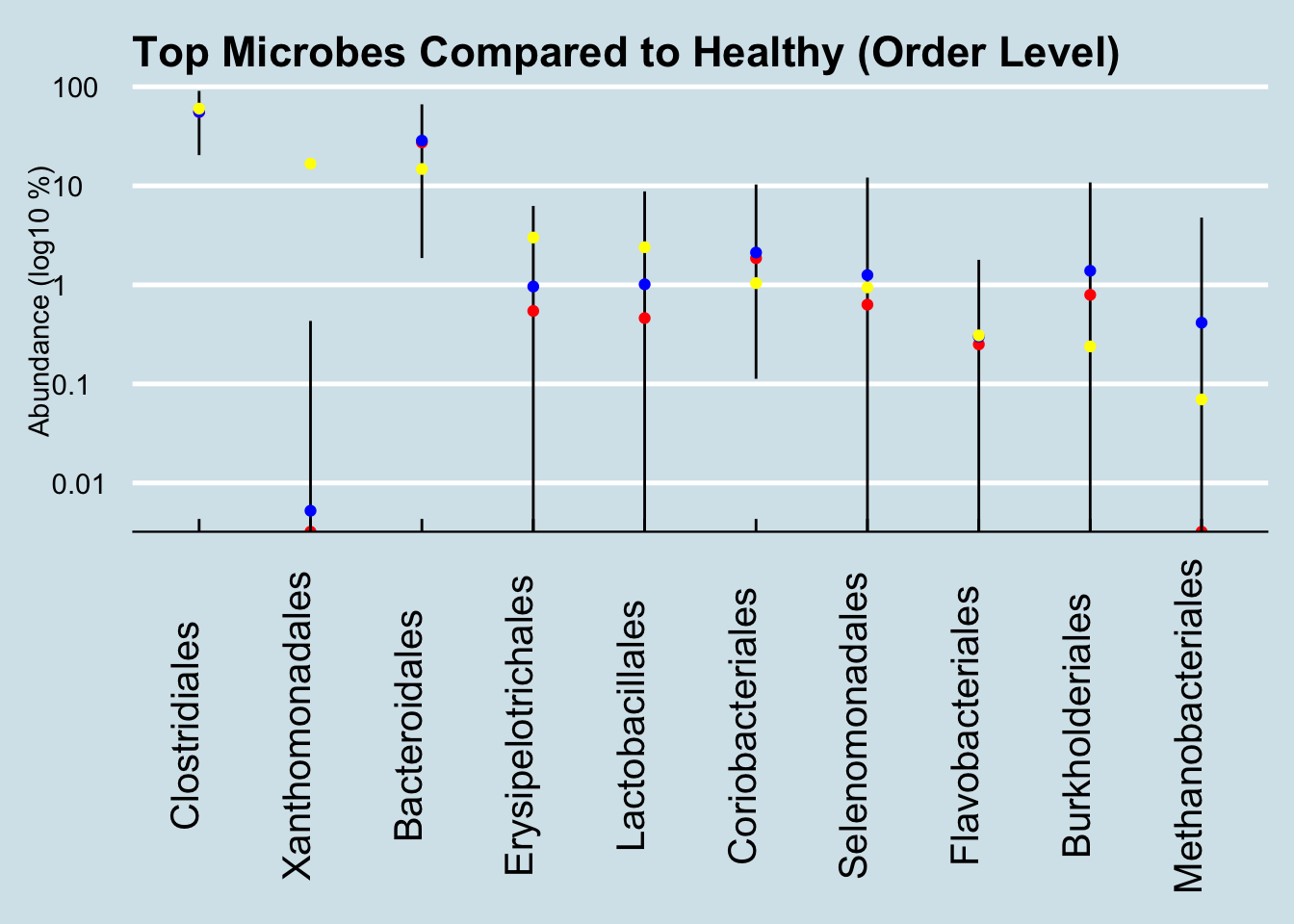

Figure 4.5: Healthy ranges compared (Order).

Here we see way, way off-the-charts high levels of the order Xanthomonadales. These microbes take up 16% of his entire gut microbiome! Of the thousands of microbiome results I’ve studied, I see this bacterium from time to time, but never at such high abundances. Other than Paul, the most I’ve ever seen in my own gut came after returning from my 2-week camping trip in New Mexico, where my total was 0.0056122. Paul’s is 2800x that amount.

Not sure what this means, but one version of that bacterium is a pathogen that lives in things like catheters; it’s usually harmless and goes away when you take out the catheter. Is Paul’s chemotherapy “port” involved?

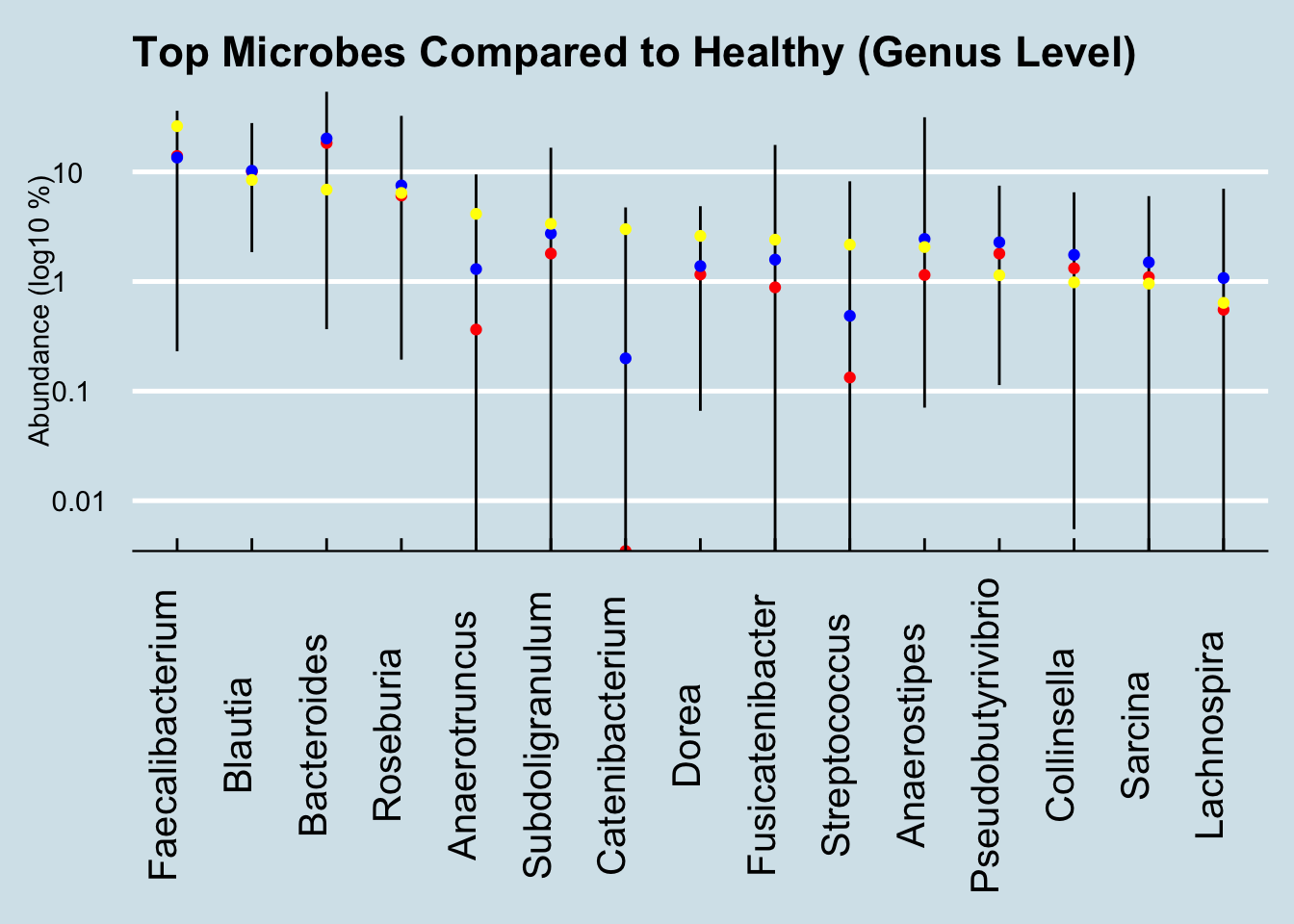

Let’s look deeper, at the Genus level:

Figure 4.6: Healthy ranges compared (Genus).

Here the one notable outlier is Catenibacterium. Intriguingly, the other people I’ve seen with such high levels are all unhealthy. One of them, like Paul, is undergoing chemotherapy. Is this a microbe that associates somehow with disease? And if so, is there anything he can (or should) do about it?

Ken Lassessen at https://cfsremission.com has compiled an extensive list of actions that can increase or reduce common microbes and he finds evidence that flaxseed oil is associated with reduced Catenibacterium. Is it worth trying? Ask your doctor.

Peer reviewed studies of colorectal cancer and the microbiome have singled out Fusobacterium. In fact, that microbe is so clearly associated that destroying it with the antibiotic metronidazole slows tumors in mice. There is none in Paul’s sample, either because his current cancer treatments have eliminated it, or because it just wasn’t detected in this sample.

New research shows that, at least in people with an inherited gene known to pre-dispose the likelihood of colorectal cancer, the gut microbiome can form a biofilm composed of slightly-mutated versions of two microbes: Bacteroides fragilis and Escherichia coli.123, neither of which is identifiable in Paul’s sample.

If you found some in your microbiome sample results, would that that mean you are at risk? The short answer is no. For what it’s worth, among the hundreds of samples people have sent me, B. fragilis ranges between zero and 4% in healthy people, and zero to 7% in unhealthy people. Pretty inconclusive at best; misleading and counter-productive at worst.

Researchers have found many other intriguing links between specific microbes and colorectal cancer, including a recent study hinting at an association with the oral microbiome: low abundance of Lachnospiraceae in the gut apparently allows some oral pathogens to get a foothold in the gut mucosa.124

Another study (Jacouton et al. (2017)) found that drug-induced colorectal cancer in mice could be prevented by feeding them a probiotic strain of Lactobacillus casei BL23. Although the research is unlikely to apply to humans, this particular strain is known to affect the immune system, producing a cascade of molecules that appear to change a rat’s response to cancer cells. For what it’s worth, Paul’s sample includes a bit of genus Lactobacillus and some Bifidobacterium too, though the test can’t tell the particular strain.

Are any of these microbial connections worth further investigation? Sadly, the chances are slim, but keep in mind that the best scientists on earth don’t know the answers either. It’s arrogant and patronizing to suggest that patients and their families should defer only to “real” scientists on these questions.

We need all the personal scientists we can get.

See more references about the links between the microbiome and cancer, two good places to start are: Garrett (2015) and Fulbright, Ellermann, and Arthur (2017)]