3.7 Do Probiotics Work?

Probiotic supplements are a $55 billion business, with food and beverages accounting for almost 80% of that, according to an August 2021 report by Grandview Research. With unregulated health claims that range from the benign (“helps digestion”) to the fantastic (“A miracle cure!”), do they make a significant difference in my own gut microbiome? I tested myself to find out.

Among unhealthy people, there is evidence that, under a doctor’s care, probiotics can help with antibiotic-associated diarrhea and similar conditions in children or among people recovering from C. difficile infections.

On the other hand, a recent scientific review of all well-done studies of probiotics among healthy people couldn’t find evidence that probiotics made much difference compared to a placebo in randomized controlled trials. When the data-heavy web site FiveThirtyEight did a week-long series on Gut Science, including a detailed survey of what’s known about probiotics, they concluded: “There’s no evidence in humans, however, to support taking probiotics just to generally improve your gut health.”

A literature review by the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality found no safety issues in healthy adults, but there is surprisingly little research to show that the pills actually do anything. The independent lab Labdoor tests most common brands to see which actually contain the organisms claimed on the label, but I couldn’t find anyone who tests whether the body can absorb them or not. There have been a few peer-reviewed studies showing that some microbes in supplements can make it to the gut96, but these studies almost feel like special cases, where they try lots of microbes and only a few make it. It’s not clear that organisms in a typical off-the-shelf bottle of probiotics have ever been tested that way.

I’m especially interested in learning whether the probiotics in the supplements actually “stick” in my gut. Taking so many billion organisms in pill form all at once may very well show up in a single gut test result, but how do I know they’re not simply being flushed out of my system? Or worse, how do I know I’m not just crowding out something more important?

To find out, I tracked my microbiome daily while taking a high quality probiotic supplement, one that I received directly from the manufacturer. To be a fair test, one worth publicizing the brand name for better or worse, I’d want to try it out on multiple people, at multiple times. Because I didn’t do that this time, I won’t name the product other than to say that it’s from a “good” brand and well-recommended.

I took the supplement once per day for nine days. I would have continued for an even ten, but I was starting to feel uncomfortably bloated those last few days. While that’s an encouraging sign that the pill is working, I didn’t want to do anything to seriously mess up my gut. I’m doing this experiment for fun, and it won’t be fun if I get sick as a result.

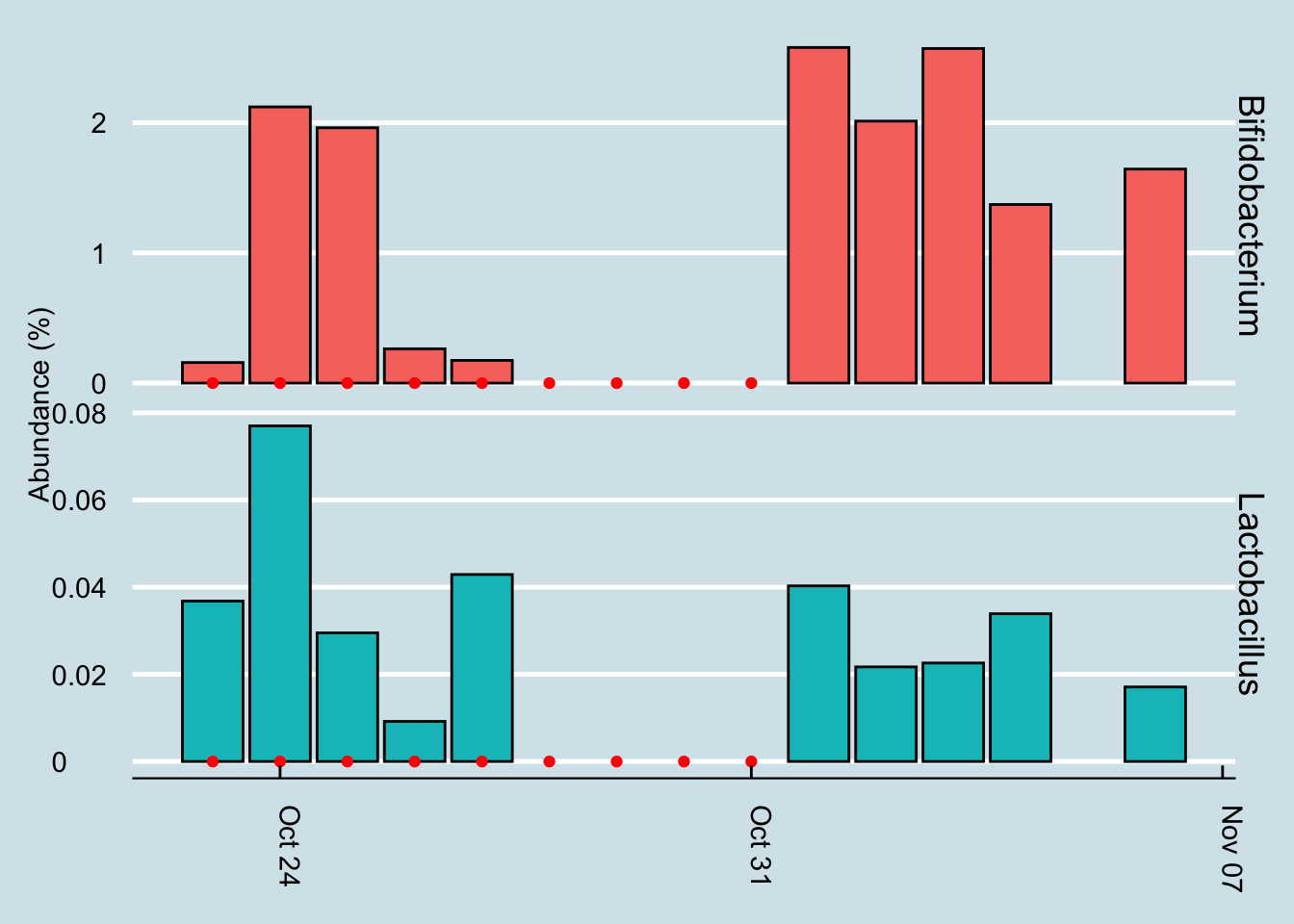

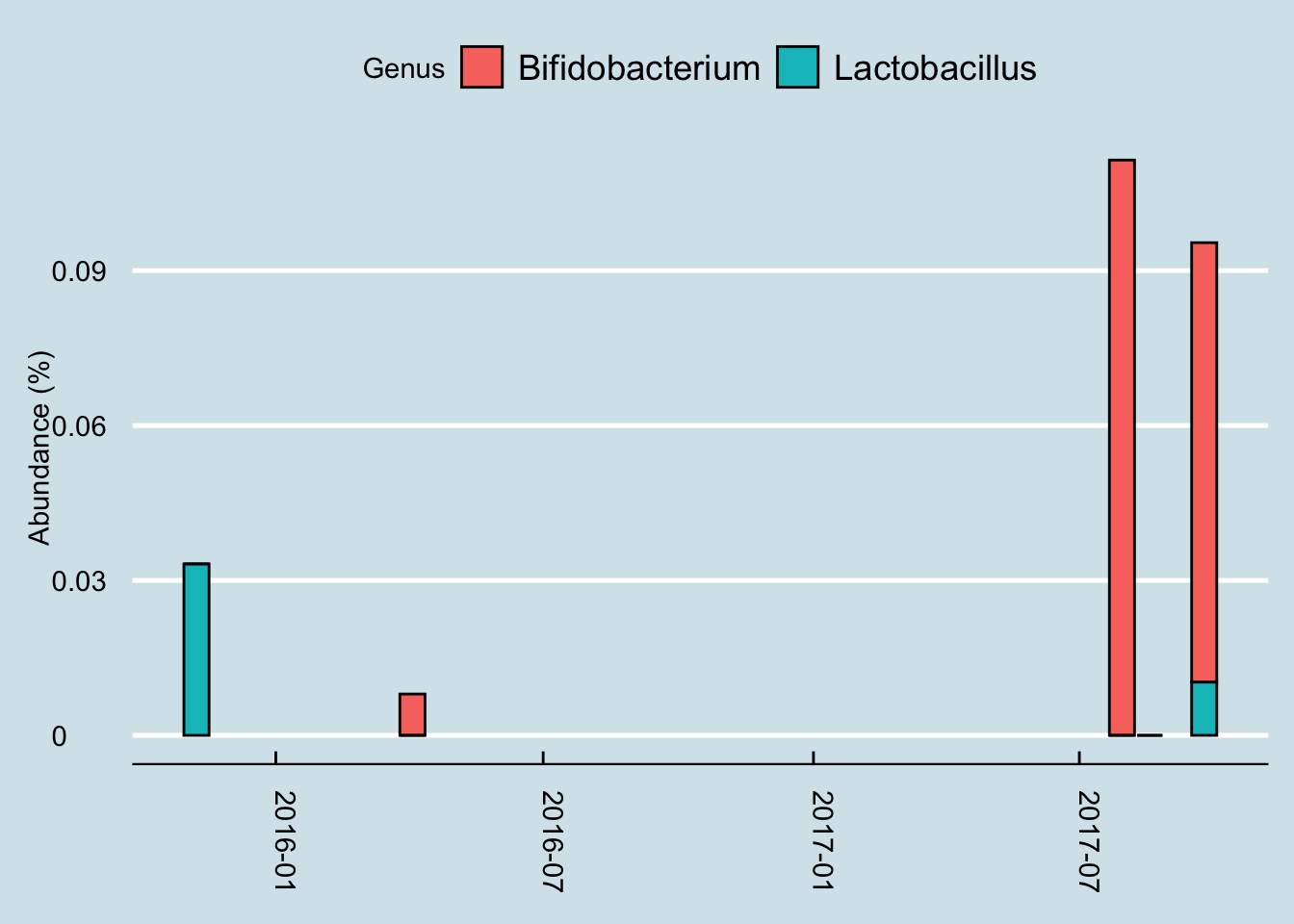

Let’s look for at the overall abundances for the two genera that were in the supplements: Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. (Figure 3.16)

Figure 3.16: Percent abundance of key microbes (genus-level) found in the gut while taking a probiotic supplement.

The red dots represents days when I took a gut sample after consuming the probiotic. Unfortunately, despite taking and submitting samples daily, several of my results just didn’t have enough reads to be useful. This chart shows only the days when I have a sample of at least 10,000 reads.

Even with that caveat, it’s hard to see clear-cut evidence that the pill had a significant effect. Yes, I have slightly more of those two taxa by the end of the experiment, but seriously, not that much more.

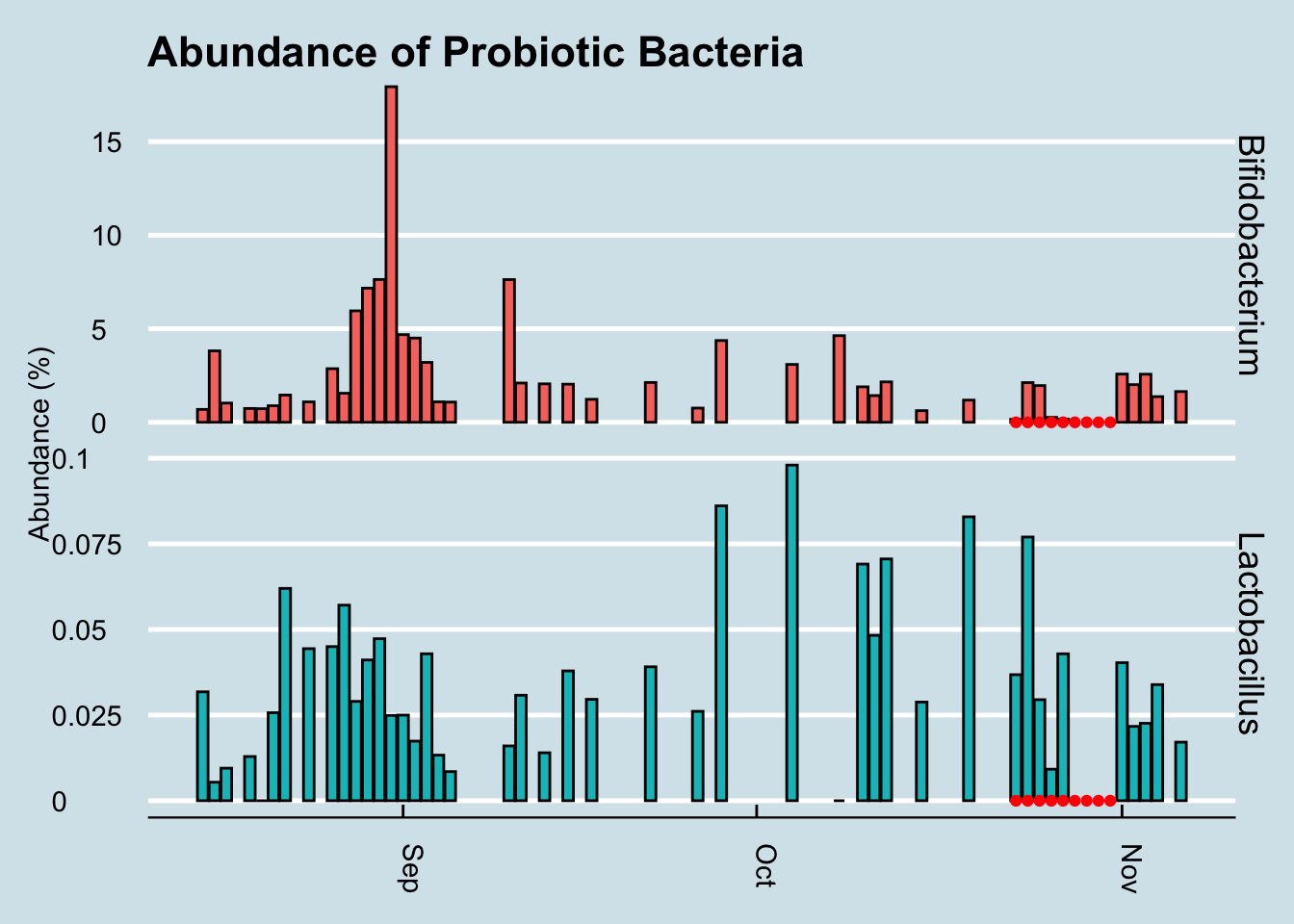

Let’s look at a longer time horizon (Figure 3.17).

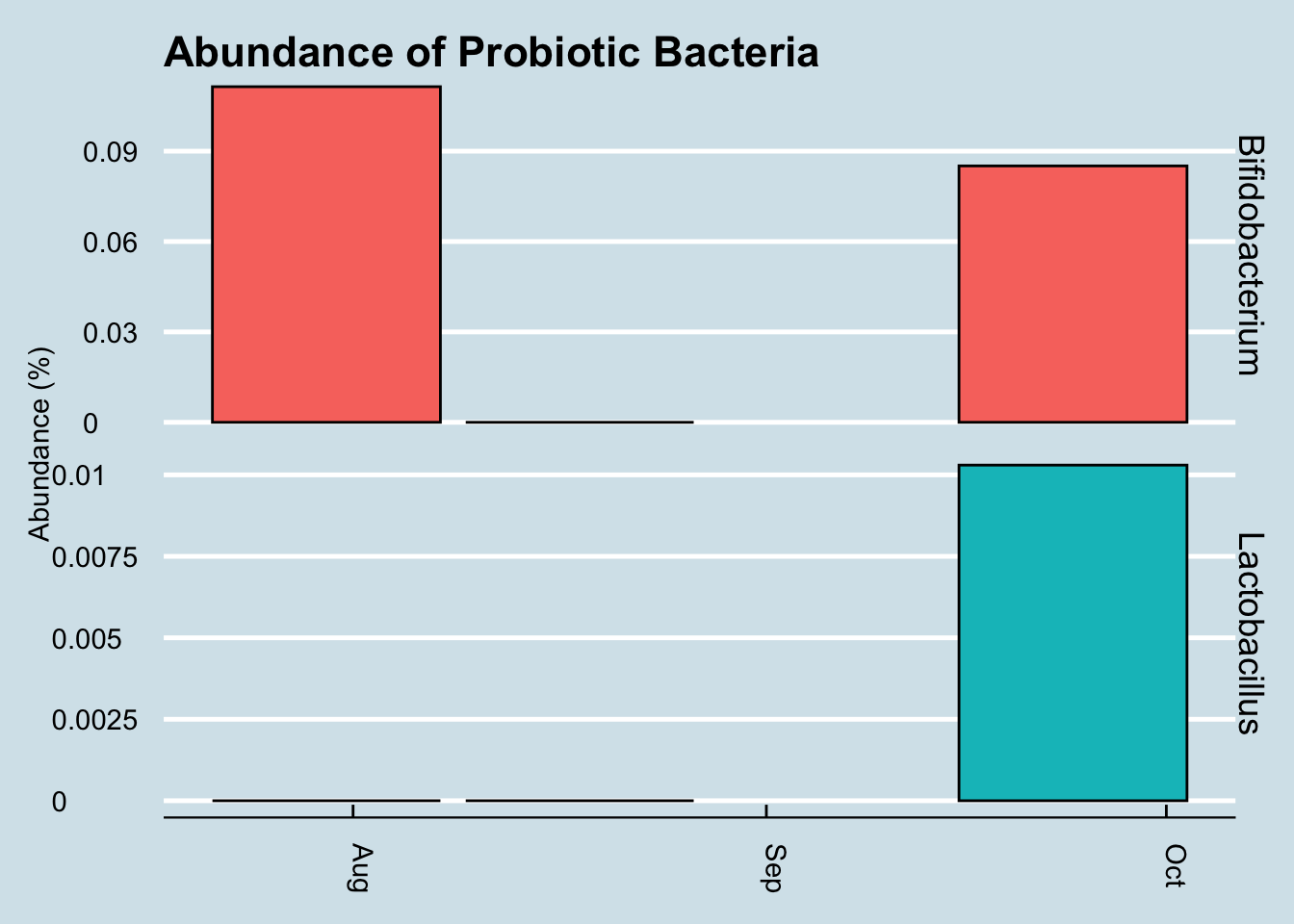

Figure 3.17: Percent abundance of key gut microbes over a three month period after taking a probiotic supplement.

Hmmmm, it seems the levels of those particular genera did increase a tiny bit at the end of the experiment, but there are plenty of other times on the chart where I see spikes too. In fact, the biggest increase happened in September when I was living it up in New Orleans, eating red beans and rice – and no probiotic pills.

Maybe my view of the microbe ecology, hoping to see results in only one or two genera, is too simplistic. We know that the gut is an ecosystem. If you add lots of one type of organism, maybe that affects the abundances and ratios of other microbes, all of whom are in constant competition with one another. Is there a way to tell overall how the microbes are changing?

Let’s apply an ordination analysis. Essentially this means we look at all the samples together and work out how different the samples are from one another, based on some “distance metric” that compares the abundances of specific microbes. If the abundances of two samples are roughly the same, or if they tend to rise and fall together, then we plot them next to each other, and vice versa if they are not well-correlated. There is a mathematical way to do this where we combine all these different correlations over and over and pick just the two that seem to matter the absolute most, which we’ll plot on a two-dimensional graph (Figure 3.18)

Figure 3.18: NMDS ordination (Bray-Curtis) of gut samples for ten months before and after taking probiotic supplements.

Hmm… that looks pretty random to me.

3.7.0.1 Other people

Since doing this experiment on myself, I’ve spoken with numerous others who’ve tried something similar: take a gut test, then start some type of probiotic supplement, and finally take another followup test a few days or weeks later.

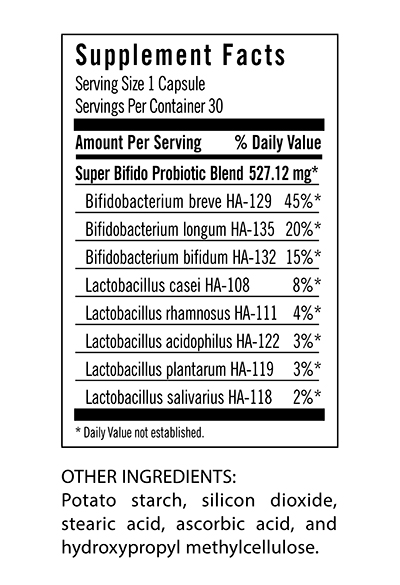

Here’s an example, “Jeremy”, a healthy man in his 50s took this probiotic supplement: $42 for one month of pills:

Figure 3.19: Super Bifido Plus Probiotics contains high amounts of live Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus.

and here’s the high level result:

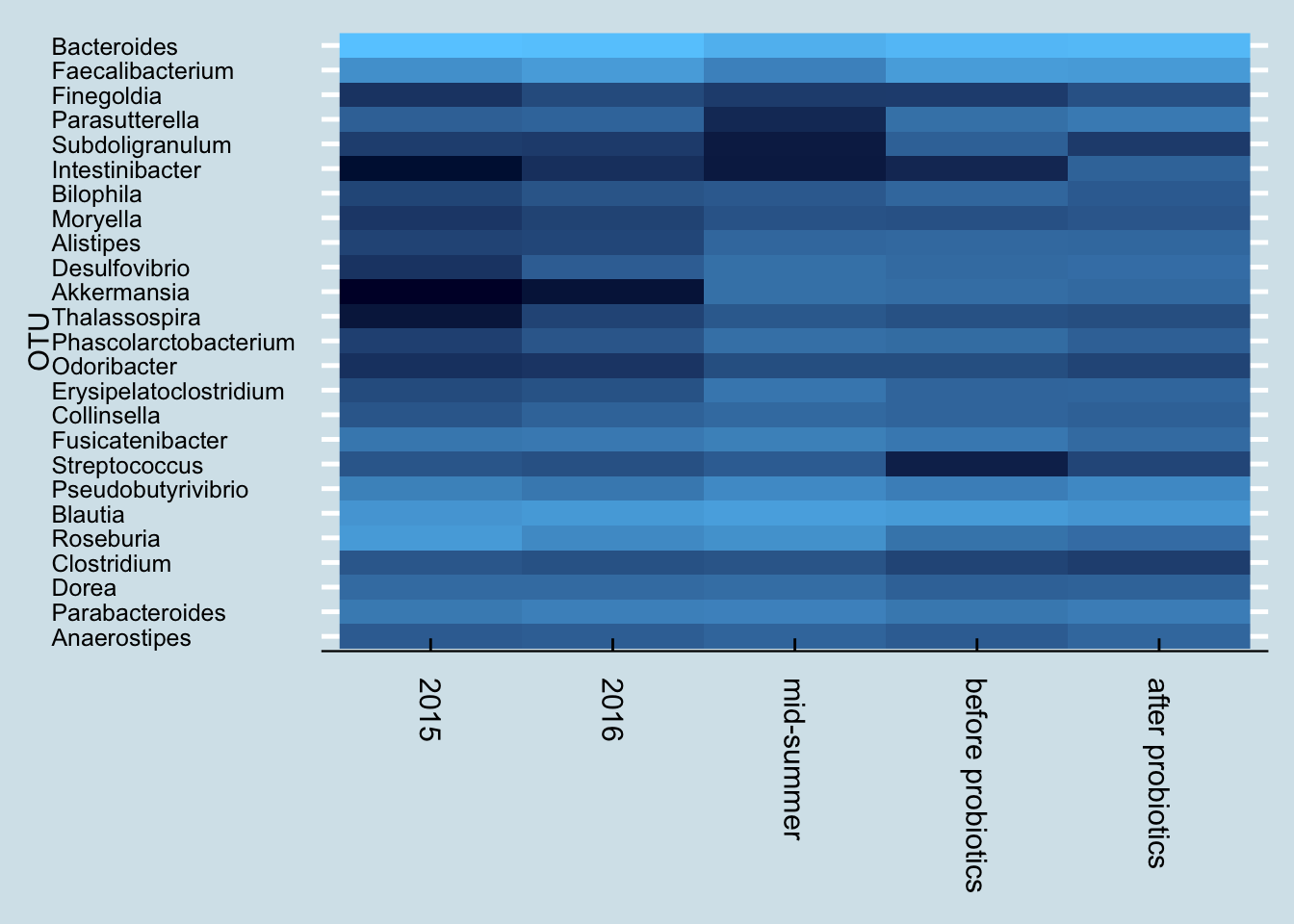

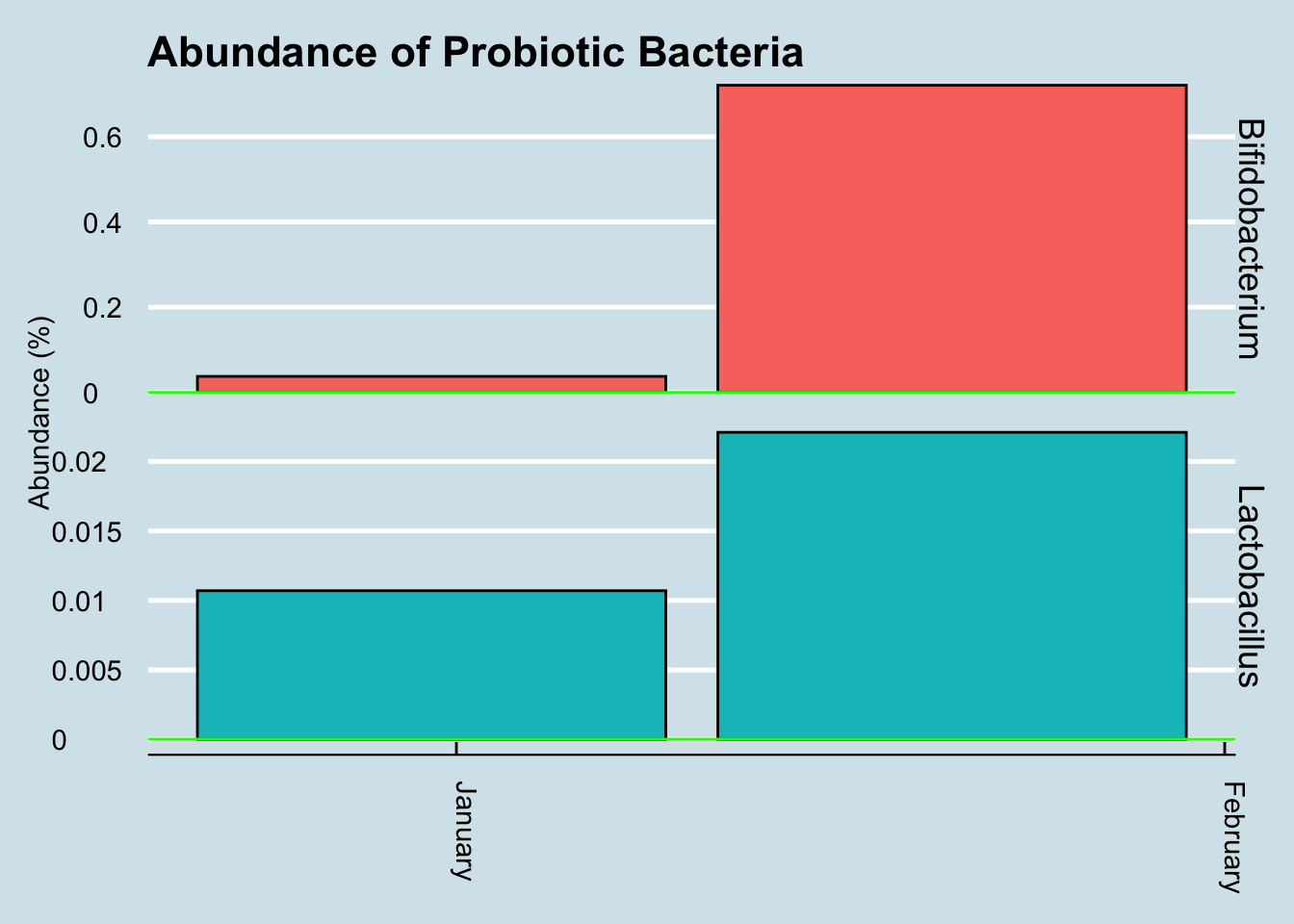

Next let’s look just at the microbes reported to be in the probiotic pills. Jeremy has three samples of interest: (1) taken in mid-summer, a month before starting the probiotics, (2) right before the month of pills, and (3) after completing 30 days of faithful pill taking.

So although we do see a slight increase in both taxa, it’s hard to pin it solely on the probiotics. After all, he was at even higher levels a month before starting the pills.

So although we do see a slight increase in both taxa, it’s hard to pin it solely on the probiotics. After all, he was at even higher levels a month before starting the pills.

Also, looking more closely at the read counts, I see that the final sample had the lowest, about 36,000 reads versus the 80,000+ reads of the other samples. When dealing with low-abundance bacteria, this can matter, but it’s impossible to tell precisely how much. The bottom line is that it’s possible that the probiotics had no effect whatsoever, and even if there was an effect, it was probably quite slight.

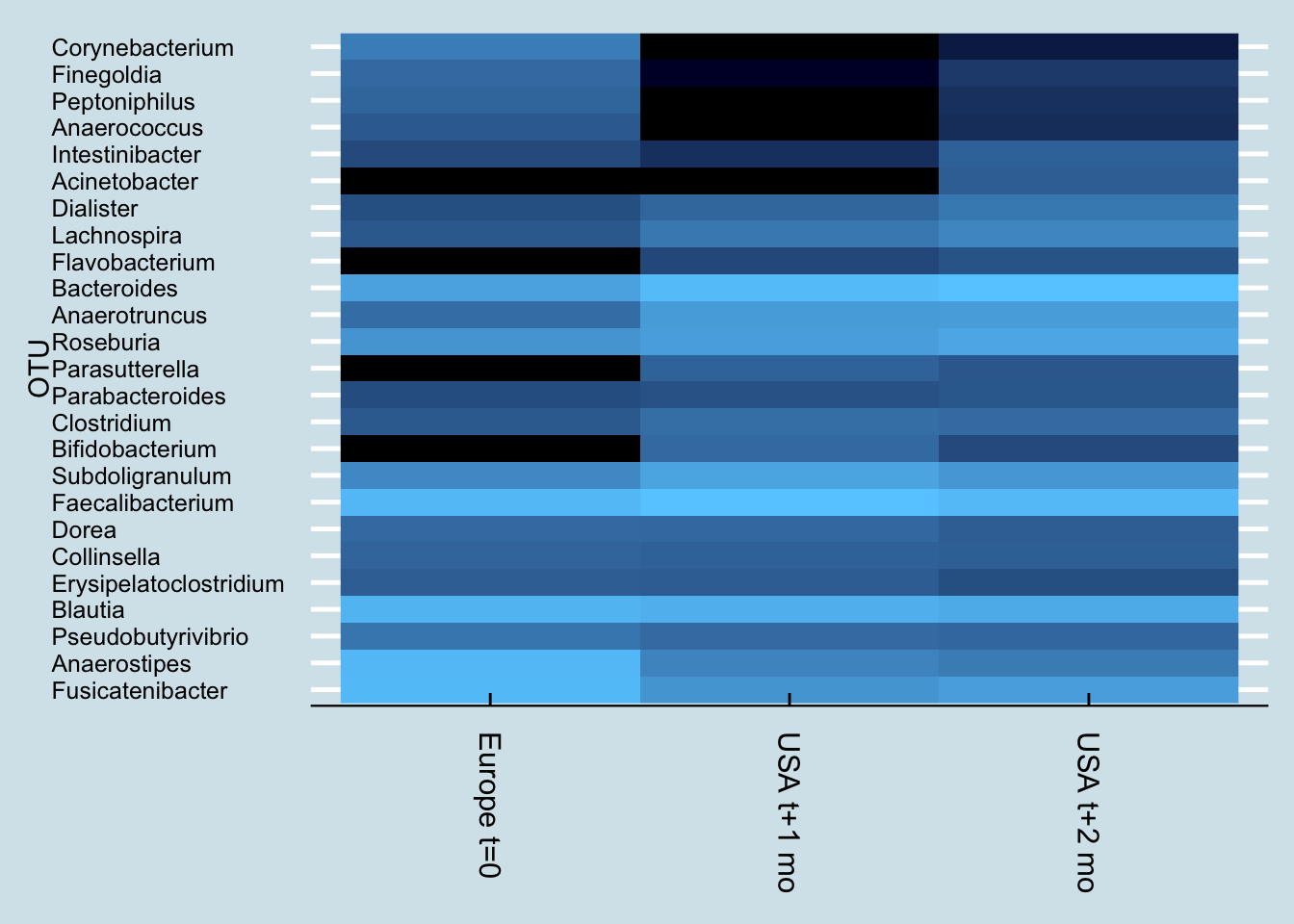

In fact, probiotics appear to have less of an effect even than travel. Here’s “Kevin”, a European man who moved to the United States.

Notice how Kevin’s microbiome shifted dramatically a month after arriving in the US. Soon after that, he began taking a probiotic supplement, but his gut – while different – hasn’t shifted as much as it did from the international move.

3.7.1 VSL

The most tested probiotic is VSL#3, and recently a woman sent me her microbiome test results after taking Optibac for 4 days prior to her second test. (Figure 3.20).

In this case the abundances of these microbes went up significantly. Is that a coincidence? Hard to tell from a single sample, but perhaps this probiotic is one that makes it through and shows up in the results.

Figure 3.20: Change in key microbe levels after a course of VSL#3

3.7.1.1 (Tentative) Conclusions and next steps

It is very difficult to say with this analysis that the probiotics had any effect that is detectable by the uBiome Explorer test.

Further analysis required:

Consider other statistical analysis. Although the two strains contained in the probiotic pill don’t appear to cause a change in the gut microbiome results, are there other changes that can be detected statistically. Perhaps there are other taxa that show a significant change.

Other time horizons. Maybe the changes don’t happen immediately. Although at a high level, there doesn’t appear to a noticable lag in the levels of the probiotic strains, perhaps a more sophisticated data transformation would uncover something.