3.20 Soylent

A team of undergraduates at the University of California Berkeley conducted an experiment with 14 people to see if the nutrition drink Soylent would change the microbiome115. They found that it increased the ratio of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes by a significant amount. How about me?

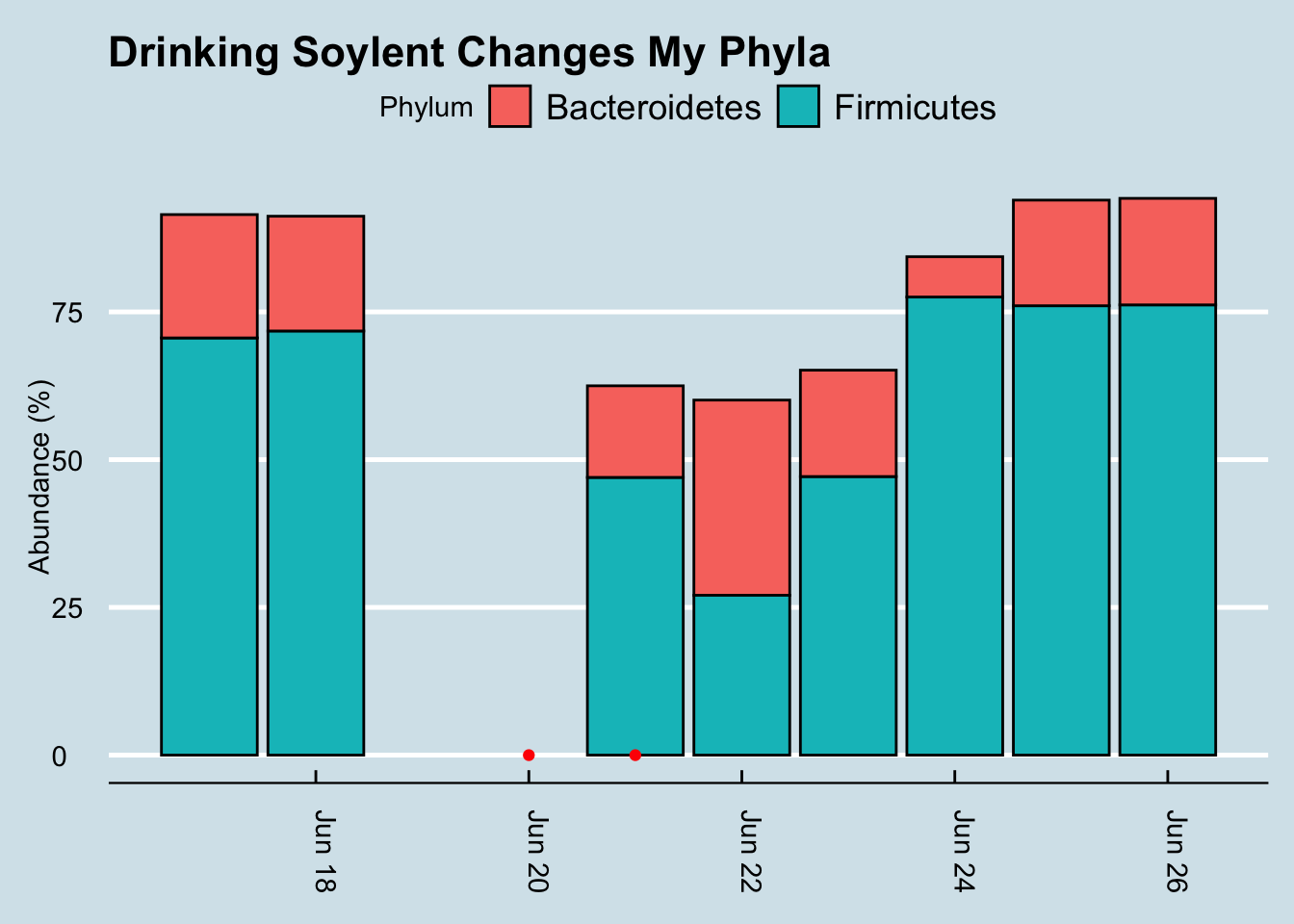

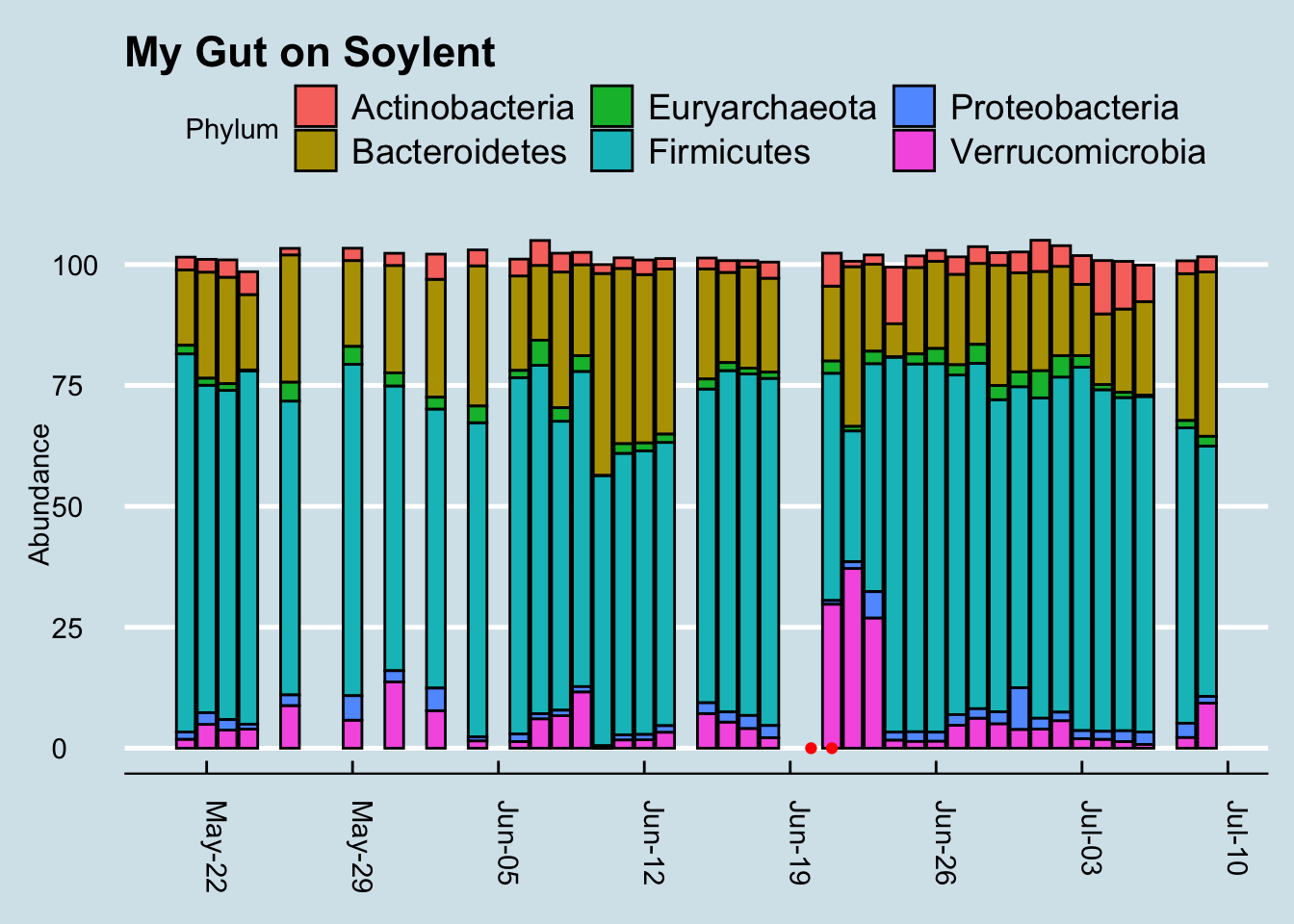

Interestingly, looking back through my daily microbiome samples to see which dates I tried Soylent, I got this: (Figure 3.46)

Figure 3.46: Red dots mark days when I drank Soylent.

The red dots are dates when I drank Soylent.116 Unfortunately, the samples failed on two of the dates in this chart, so I’m unable to see how my gut microbiome looked immediately before taking the Soylent, but still, isn’t it strange that my F/B ratio was reasonably stable until then?

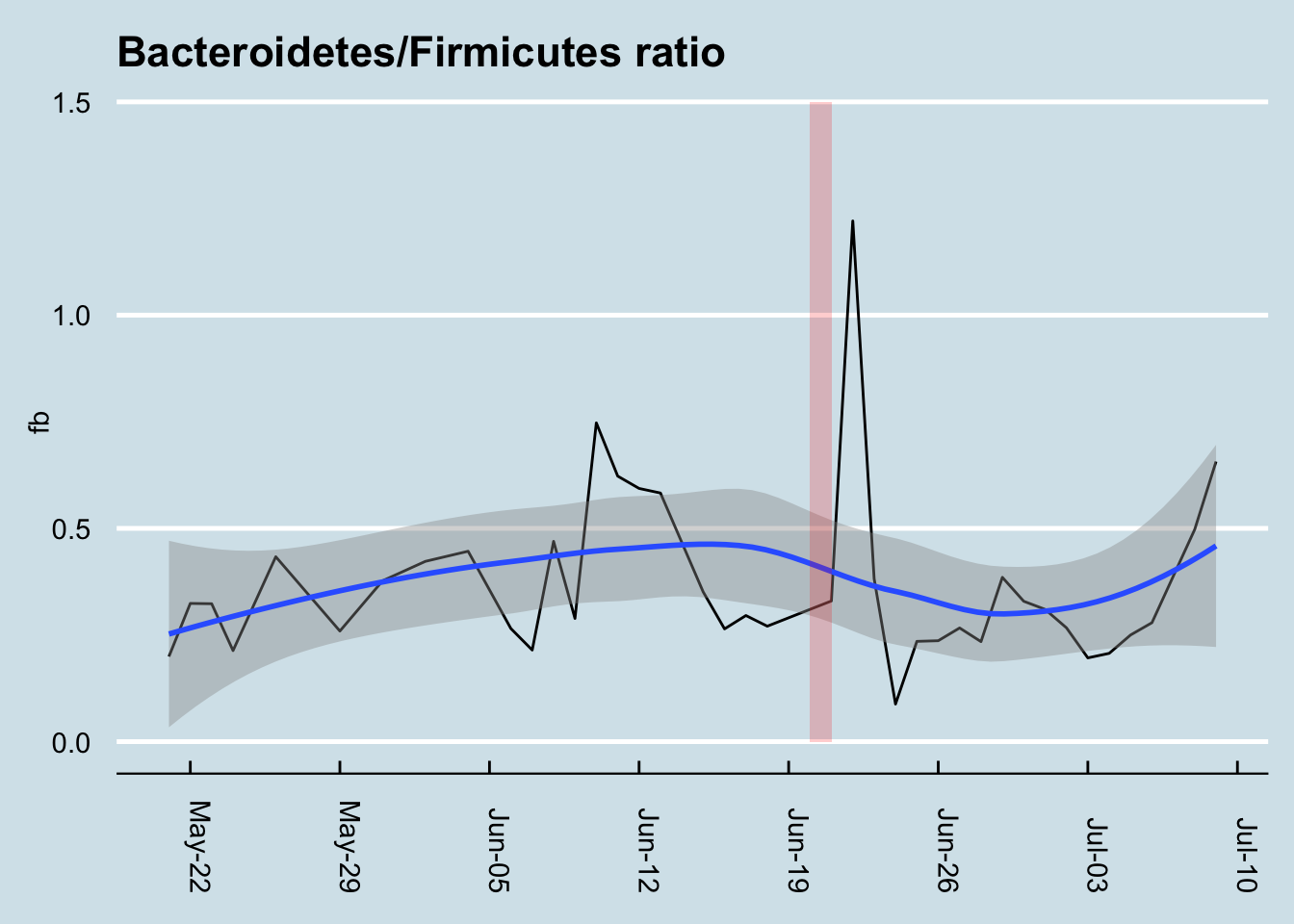

The shift is more dramatic if we look at a longer time frame, the weeks before and after the Soylent drinking (Figure 3.47)

Figure 3.47: Soylent-drinking days are highlighted in red.

This is by no means a confirmation of the results of their experiment, since mine was just an ad hoc test for two days among many other types of food-eating and tests that I regularly conduct on myself. That said, it is odd that I find a significant shift in that ratio, in the same direction as in their published trial.117

Why would this be?

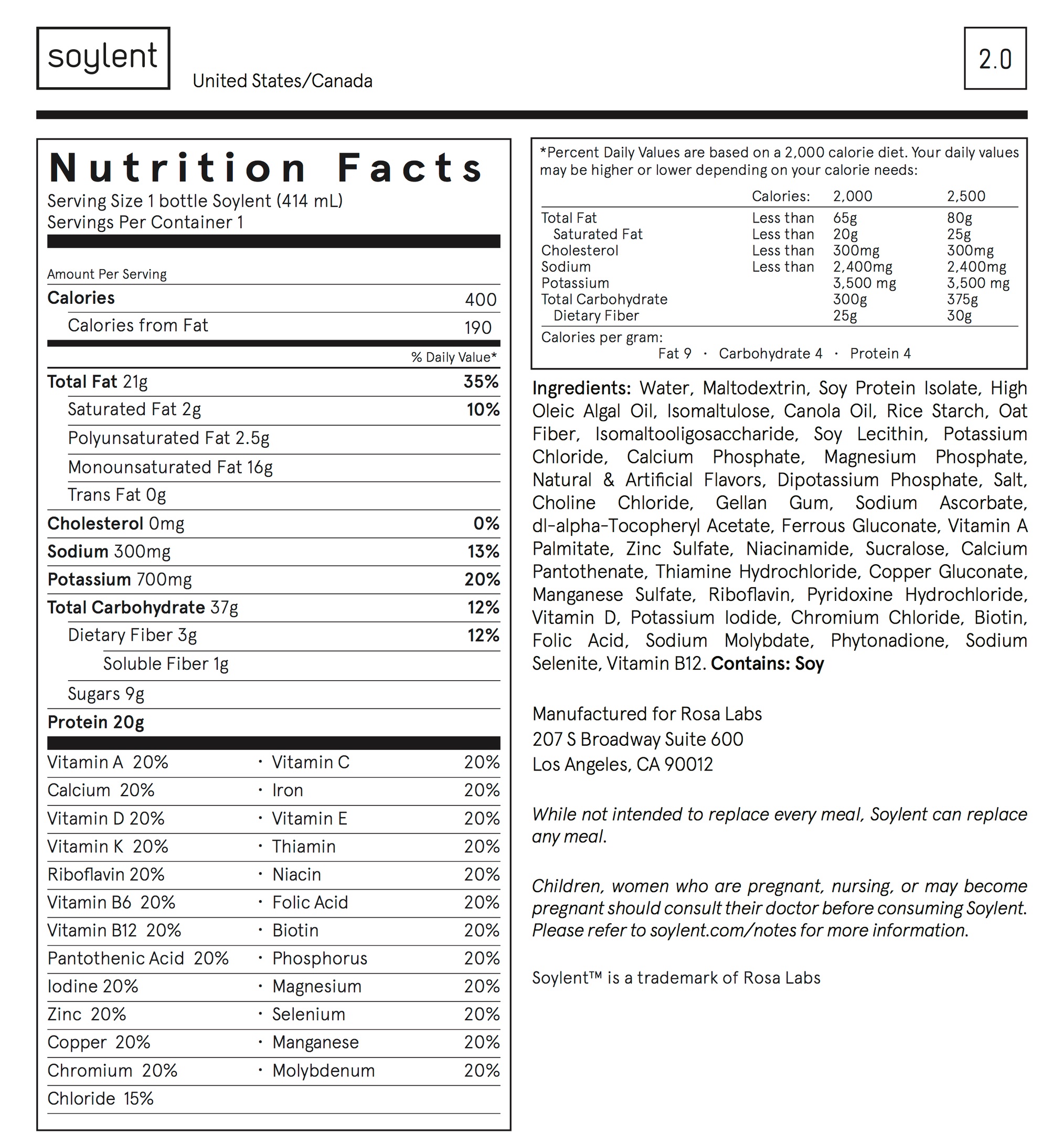

The nutritional label gives some possible clues. (Figure 3.48)

Figure 3.48: Nutritional label and ingredients list from a bottle of Soylent.

One of the main ingredients, maltodextrin, is a man-made polysaccharide popular as a food additive for its usefulness as a thickener and texturizer. Usually synthesized from corn or wheat, it has been added to food products since the 1950s and is now in something like 60% of all packaged foods. It also has some well-known effects on the microbiome118, at least in mice, and on the ability of some bacteria to form biofilms. I couldn’t find any studies in humans that specifically look at the affect on the microbiome, except now this Berkeley study.

The Soylent web site explains that the maltodextrin is there to provide carbohydrates. Mixed with oat flour and other fibers to give it an overall lower glycemic index, it’s naturally easy to digest and a quick source of energy. That sounds like a recipe that should significantly affect the microbiome, especially if you use it, as intended, as your main source of food.

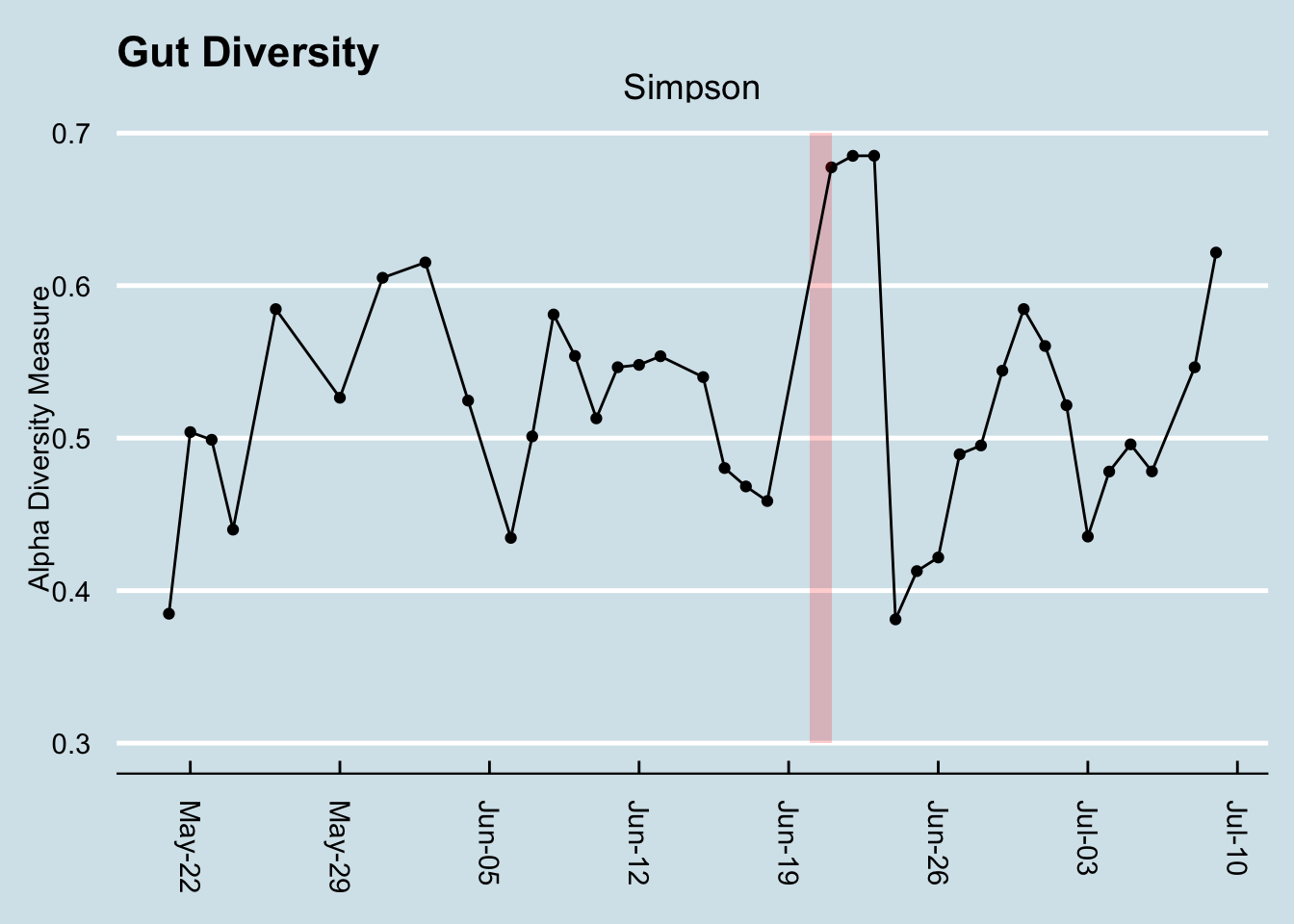

Interestingly, my gut diversity seems to have increased sharply right after drinking the Soylent, followed by a crash a few days later.

Figure 3.49: Family-level diversity. The period highlighted in red is days I drank Soylent.

The diversity calculated in this chart is a very crude measurement that tries to summarize a complex ecology into a single number, and as you can see it tends to vary sharply from day-to-day anyway. That said, it’s not that variable over time, and the few days after Soylent seem notably higher than the rest of the period measured. I’m betting this is really caused by the fact that I was visiting another city at the time, so the increase is likely related to travel more than the food itself. Still, something for future research to consider.

Finally, let’s look at the overall phyla-level breakdown. (Figure 3.50)

Figure 3.50: Phyla breakdown shows high Verrucomicrobia after Soylent drinking. Genus is Akkermansia.

Interestingly, the days after Soylent drinking show that the Firmicutes has been replaced by Verrucomicrobia, the phylum that contains Akkermansia. The affect lasts a few days, and it’s unusual compared to the rest of the sampling period, so I doubt it’s a coincidence. Still, it’s very hard to tell the cause.

More details are available on the Mycrobes site of the student group that did the experiment. There is also a lively Reddit discussion.